|

Interview with Jonathan Altman

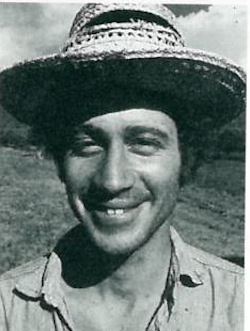

Jonathan was a Suzuki Roshi student at Tassajara early on and, though he has lived in Taos or Santa Fe, he's always remained a good friend of mine and of the SFZC. He has been a supporter of Shunryu Suzuki archiving even though he doesn't believe in it, is more of a mind to mind, warm hand to warm hand transmission type but also he's loyal to his buds from the past and present. He was a founder of Lama Foundation. His wonderful wife Kathleen died in recent years. Their son Gus was born in 1977. Jonathan was the first or one of the first interviews I did. He really didn't want me to use a tape recorder but I got him to do it anyway. Later I interviewed lots of people with just taking notes. Oh yes, he's a fine artist. I'd love to add some of his art here but I bet he wouldn't want to have them digitalized.. Another thing. Daya's and my son Kelly was, we are sure, conceived at Jonathan's home in Taos in early January of 1973.

The lamas I've met - their consciousness is far beyond any Zen master that I've met beside Suzuki Roshi. In Tibetan Buddhism everything is body speech and mind. Body is Nirmanakaya, Speech is Sambhogakaya and mind is Dharmakaya. And they say outer, inner and secret teaching. And everything they do has an outer, inner, and secret meaning. This is Vajrayana. So everything takes place on those three levels. It's not like you go from one to the other to the other. But without formal initiations you can't practice the secret meaning and that requires transmission, some kind of formal empowerment, and also on the part of the practitioner, a samaya. Trungpa used to tell people if you break your samaya you can go crazy and you can make your teacher sick. So the teacher has to be careful who he gives the vows to. There was a great reciprocal responsibility that's taken in any ceremony. DC: Barbara in your house in Arroyo Seco told me about when Kobun's daughter went to Tassajara and everybody thought it was going great, she was calling Barbara everyday telling her they're not telling me anything. They haven't given me zazen instruction. Nobody's asked me anything. Zen Center mush versus Trungpa’s specific teaching. And Barbara said that as a meditation teacher with that group she knows that if Koko had of gone to any of their places that she would of had an instructor to relate to who would have checked with her how is she doing and what's her understanding of her meditation and this and that and Trungpa didn't let her take vows till she was ready for it. There was a lot of accountability. JA: In Zen you chant Bodhisattva vows from the beginning. You're not expected to understand them but as your practice deepens your understanding will too. DC: The anti-intellectual aspects of Zen Center don't necessarily exist in other countries. They study a lot. They have their own balance but we take what we want. They don't give up the words till they've studied them. Suzuki was a real scholar but he didn't care if we studied much or not. JA: It depends on each student and the capacity of each student. My understanding is very close to Zen as Suzuki Roshi taught it. But the teachers that I respond to are Tibetan teachers and sometimes they have this extraordinary tangible emptiness and compassion. Very large beings. But then you get involved with the Tibetans and they say you have to do these 100,000 prostrations and this and that. That's for purification and if you receive the teachings before you're purified you'll either be hurt by them or you'll corrupt them. DC: When Katagiri Roshi and Tara Rimpoche gave a workshop together at Green Gulch, Tara listened to one of Katagiri's talks and Bob Thurman whispered translation in his ear and when Tara gave his talk later he said I've always wanted to hear a Zen talk and I'm amazed and what I've heard. He started at the top. JA: That's right. Everything in Tibetan is this extraordinary hierarchy. Everything starts at the bottom and you work your way up and the highest teaching is no teaching and effortless effort. Except there's a difference. Suzuki Roshi once said, "We enjoy the movie, but we also enjoy the blank screen." In reading about Dzogchen I think they have a way of turning around and seeing the light directly - the projector. At the end of practice period at Shosan when everyone asks him a question I asked my question which was the question of my life. I marched down there and I threw myself down and I looked up and I looked into his eyes and it was as if I was looking out into the universe. And he answered my question and I had no idea what he said. When you cross the boundary into another world, you're aware of something but it's very hard to bring that back. When you know it you can't say it. On this side you can say it but you're not in it. It's very hard to cross that boundary. The guards of the boundary make you give up all your possessions and you go across. I had it but I forget. They wouldn't let me take it with me. When I sat tangaryo [initiatory all day sitting], it was very hard and I didn't want to do it. I went to Tassajara for a month so I had to sit for three days. It was '68 or '69. It wasn't a practice period. It was after it in April or May. It really bothered me to have to sit tangaryo and I talked to Peter about it and he explained it was like one of the ordeals of the American Indians that you had to go through before you entered into the practice. At lunch time in my break I wandered down to the end of the cabins to look at the stream and I saw that it was always changing and it was always the same. And then I started walking back to the zendo and I saw all these people up in the garden and I wanted to tell them you don't have to do this - you're already perfect and I couldn't tell them and I went back into the zendo and I wept and wept and wept. Like two years later when I told Suzuki Roshi about that he said that was an enlightenment experience by the stream. There's something that's never moving. It's always perfect. And a wish to perfect it is a defect. DC: Suzuki Roshi talked on both sides of that. Like he said that Buddha is never satisfied, he's always trying to do more. JA: Suzuki Roshi used to say, it's a two edged sword and as soon as you use it to strike something, you cut yourself in half. Then he would start laughing. The first time I encountered Suzuki Roshi was in Menlo Park in the East West Bookstore. There were all these pictures of all these gurus on the walls, big pictures high up. There was Gurgieff, maybe Krishnamurti, who knows. But there was one picture I couldn't identify and that was Suzuki Roshi. It was the fall of '68. And I went to see Ann Armstrong [psychic] and one of the things I asked her was how can I find a spiritual teacher and she said, I don't see anybody in this country who can help you but I see one old man in the Orient, maybe he's in Japan. Then she came out of her trance and said, do you know Richard Baker? I hear he's going to Japan very shortly and maybe you should speak to him and I went to see Richard and he said that they make it very very hard for you in Japan. He was living on Fillmore Street on the second floor and he was packing. He said, you should sit here because it's much easier and you can find out if you like it and so forth. He said when they sit with Americans they sit twice as long. So I went to Zen Center and began sitting and there was Suzuki Roshi who was this picture I had seen in Menlo Park. So I sat there and he came behind me for the early morning greeting and I didn't know what to do and he paused and said, "greeting." I liked the way he bowed to everyone on the way out. He would lecture downstairs in the big room with all the pews and he'd laugh. He laughed a lot in the middle of lectures. He apologized for being such a good teacher. He said, I'm too nice. He was talking about that wonderful quality he had - there was such love for him, devotion and he was serious. DC: Maezumi Roshi once told me, Suzuki Roshi's too old to be a good teacher anymore because he's too kind. Younger teachers will be more strict. JA: All that strict stuff is really hard for me. I don't like all that macho samurai stuff. Why can't you get up and leave if you're really sitting well? DC: There was the Japanese statement, for a monk who enters a monastery, maybe it's an Eiheiji thing, "Don't say no for five years." So there was some idea that you could do what you wanted at some point. I think a lot of American Zen Buddhists are going to go to their grave saying anything they don't like is just their ego. JA: When I would hear Suzuki Roshi talk I'd say yes yes yes but then I'd say why is there Buddhism? Why can't we practice without Buddhism. One day in the Buddha hall at Page Street and they were reengineering how to enter the room and Dan W. was helping out and he was always the super sergeant, the most upright straight arrow guy. And all of a sudden this girl came in and she had lipstick sort of smeared over her face and you could see she was crazy and he started screaming at her, you go over there and she was just looking at him and at that moment I wanted to tear down the whole building. He didn't understand what was happening. Who cares what way you go. What was important was this woman's suffering at that moment. I told Suzuki Roshi about that and I was crying and he said, that's the true spirit. I always had a very hard time with the forms. So why can't we have the teaching without the wrapping? It's like Tibetan where what you encounter is this medieval world which is completely intact. You encounter that in Japan but then so much is modern. But the Tibetan picture is completely unified. Sometimes I felt like Suzuki Roshi had on a Japanese mask and he did so out of compassion because where he really was was like a black hole. It would so terrify us if we could really see who he was that he kept the mask on. When I was with him alone once up in his room in Page Street it was like each moment he'd never seen me before which was very disquieting to me. Ordinarily I didn't see that - there was just this guy shuffling around the building in his slippers. But there was always a quality that there was something terrifying there under the very dark black very luminous eyes. The thing that was most compelling about him overall was his simplicity and the fact that he was totally there and a quality of humility that undoes you. All of your things drop away because of that. We're just here. There was something phenomenal about him that you couldn't put your finger on and there was something perfect that you couldn't say what it was. He effected us very deeply. There were all these students that couldn't stand one another often or who would never otherwise be together and they were all devoted to this little Japanese guy. Dick wasn't there the first two years I was there because he was in Japan and then he came back and borrowed my car to go to Esalen and teach a workshop. DC: Yeah, he stopped by my place on the way and Niels was there and Dick was saying he didn't have any money and I said I'll give you ten bucks and Niels said I will too so we gave him twenty bucks and he was going no no no and Niels started going, "What's the matter, can't you accept a gift?" JA: There's one person who I feel got his teaching in a kind of extraordinary immeasurable way and that was Issan. He radiated that. He came out here when he was doing his transmission with Dick and he gave a lecture at the Chorten and I was so moved I was just in tears. And it was just his absolute naked beingness and his ability to be that. And somebody came in and she didn't know why she was there and he said, it's good to see you. And so much was transmitted at that moment that everybody there felt it. And he talked about having AIDS and how grateful he was because of how that helped his practice. He had an extraordinary capacity for being and an enormous compassion. And I felt that Issan got it but I don't know if Dick got it. I want Dick just to be here and to drop it all and just be suffering with us. Issan said that every time he was with somebody who died he renewed his vow to settle into ultimate closeness with everything. That's an extraordinary expression of the Bodhisattva vow and that's more important to me than the wisdom. I think Dick is deeply in the wisdom end of it. DC: Issan had the ability to be around a lot of suffering and not let it cripple him in any way. He could seem heartless. His compassion wasn't superficial. He didn't get involved with people's suffering in an unhealthy way and he scoffed at pity. JA: Suzuki Roshi used to talk about soft mind a lot. The way Spanish broke horses was to beat them till they broke them and the way the Indians broke the horse would be to put their hands on them and they would touch them all over. I agree with you that Zen Center should have practiced with a disgraced Zen master. DC note: What Jonathan is referring to here is that when there was a revolt at the SFZC over some of Richard Baker Roshi's behavior, I was living in Bolinas and not too involved in all the discussions but I went to one public meeting at the City Center and said that now people can see the problem with idealizing a Zen teacher, putting him way up on a pedestal and not realizing their responsibility to themeselves and to the teacher to keep him in check. All sorts of problems arise. What you should do now is to find a disgraced teacher so that you won't have that problem again. Oh, look - we have one here. Richard Baker is a disgraced teacher. He can't fool you anymore. He'd be the perfect abbot for the SFZC now. JA: There was Dick and Yvonne and Silas and Tim Buckley - here are all these great beings with their angry minds and whatever and it was so rich and so chaotic and so crazy and then all that richness disappeared and then there was a much more efficient machine. And I missed that enormously. It's not Dan - it's Dan and you and Peter - it was all of us and working on each other in a powerful situation. I feel very fortunate and I miss that and what I miss is the craziness. And with Suzuki Roshi who had that extraordinary enlightened quality and was like the father for everybody. And he cared a lot for the people like Bob Halpern. He was very upset when Bob went to Mexico with Alan Marlowe. He cared a lot about him. I never think of Reb - we were never at the same place or I didn't notice him. Part of Richard is sociopathic. He didn't understand the laws or being part of them but he wants to appear okay. We were all sitting around in the dining room - it was my first practice period - and I had a question about eating. That was a problem for me. Why did we eat so fast? I could never enjoy my food. We got in there and I had to chew my food double time to get out. And Paul looked at me and he said, I think we should eat in half the time. And Suzuki Roshi said, maybe you should take less food. Suzuki Roshi was right and Paul's was another trip - we're going to make it harder. There's a kind of fascism in Zen that's dangerous. But everybody sees it from their perspective. Dan thought that if he relaxed that everything would fall apart but he was talking about Dan. He was such a faithful student and then he rejected it and then he was dressing like a gunfighter out her all in black like he was dressed to kill Richard. There was an extraordinary mandala around Suzuki Roshi when I knew him which was only the last three years that included disparate elements but they were all included and that made it enormously rich. Niels is fantastic. Wonderful spirit and yet crazy. I used to see him on the roof and he'd be panting like crazy. DC: Yeah, a great artist. And yeah, lots of crazy. Once at Tassajara Alan Marlowe was angry and we were working together and he was mad at the officers, and he said, I'll show those fuckers, I'll outlive every one of them and I'll spread their ashes out over the hogback. JA: When I met Trungpa I felt like I was with the exact same person as Suzuki Roshi. I never figured out why he would want to create the scene he did at Boulder. I had this ambivalence about Trungpa. I really loved him but not his scene. I left Zen Center just after Suzuki Roshi died but that was because I fell in love and moved back to Lama. [Lama Institute near Taos] I remember weeping at the mountain seat ceremony. I remember Barbara (?) being there and her saying she saw him on the stairs and he turned around and was bowing and it was very painful for him - he had to be helped. My understanding of Zen through Suzuki Roshi is that it's pure activity. Nobody's doing it but you have to keep doing it out of compassion. It's giving you the cup of tea without the reflection that I'm doing it. And then everything is doing that and nobody's doing it. And it's very important to support that activity. You don't just go into quiescence. There's nothing extra. Nobody's doing it and there's no residue. [Here JA says something about David Padwa that I didn't understand] At the same time I want to throw out all the religion - but I feel grateful to the Chorten - I love it. DC note: The Chorten is a small Stupa consecrated by Dudjum Rimpoche I believe and built by David Padwa next to his home . It's surrounded by a wall and there are rooms, one of which was used as a Zendo for years. The home was Richard Baker's now Joan Halifax's but the Chorten remains separate with its own board which Jonathan is on. When I went to live in Santa Fe for a year with Elin and Clay (July 92-July 93), the first thing that Jonathan did was to take me to the Chorten. I'd been there before but he wanted to show me how it was then and how much it meant to him. Baker Roshi disciple Russell Smith was living there. I said I'd take care of the sitting there every Wednesday at 5:30 and did so with Elin for that year. JA: After the first sesshin at Tassajara when I was in practice period, I saw Suzuki Roshi maybe thirty feet away and this huge smile came across my face and he called me over and he told me to go and get Yoshimura, the priest who was a baseball player, so I went and did that and he didn't know what I was talking about so it was strange but I think Suzuki Roshi wanted to see me and just made up something for me to do. The last time I saw him I went to see him in an interview and I wanted to know my relationship with him. And at the end of the interview he said you can have another interview and at the end of that he said, "You are my disciple." I don't know what that means but I remember that. DC note: Suzuki Roshi said to me that he had students and disciples and that the disciples were the ones he had ordained as priests. But some people whom he had not ordained he would say were his disciples - like Trudy Dixon. He didn't say it much. JA: Suzuki Roshi would have worked with Dick for a much longer period of time. Yvonne said his instructions to Dick were you should go to Tassajara and stay there for a long period of time. You should refine what you have. The first sesshin that I sat, after about three days. All of a sudden there was a moment like when somebody turns off the sound, where everything became sound and I was one with the sound. It was a different world. But I couldn't come back. I didn't know where I was. I had an encounter with Paul Shippee. There was this intense practice and I felt like I was inside it. But most of the time I was in reflective mind, my little finite petty life. I had a very strong connection with Yvonne. I used to work in the office that first year. She set it up so I would drive Suzuki Roshi down to Tassajara and drive him back - he needed to go for a day. There were a lot of people in the car on the way down and on the way back it was just he and I. He sat in the back. So we talked and one of the things I said was it's very funny when you lecture, before you say anything, there's one thing, but as soon as you start talking there are two things. He said, you're right. That's like a koan for me. When he explained things in his lectures I'd sometimes get irritated and think you're saying too much. When I went to see him for that interview he said, You're okay. He said it three times. One of the reasons that I liked to hang out with Yvonne was that she was so close to Suzuki Roshi and she hung out with him and she'd tell me stories about him. I have a strong feeling about family - you and Yvonne, Dan, Dick, Peter, Joan Halifax - we've all shared an understanding and it moves me very deeply and we're also all screwed up which is okay. We're part of an emerging consciousness. It all changed around 1945 and the atomic bomb. You'll have memory implanted in you. In time we'll have a kind of leverage we never had. We won't be able to wipe out the whole biosphere. There's a whole new area and we've got to integrate these teachings and we don't have centuries to do it. If we don't then the whole show is over. DC: Let's just follow our intuition and not get too big a sense of urgency. JA: Yeah. Yeah. |

Jonathon Altman

Jonathon Altman