cuke.com

-

Shunryu

Suzuki Index -

WHAT'S NEW -

table of contents

-

cuke.com

-

Shunryu

Suzuki Index -

WHAT'S NEW -

table of contents

-

cuke.com

-

Shunryu

Suzuki Index -

WHAT'S NEW -

table of contents

-

cuke.com

-

Shunryu

Suzuki Index -

WHAT'S NEW -

table of contents

-

David Schneider writes

David Schneider

cuke page

Posted Feb. 3, 2019

|

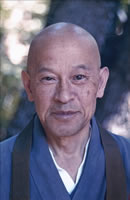

Dwelling Place of the Ancestors The way it worked was that you paid money

to go labor all day at menial tasks. Some people saw it that way, notably

parents of a number of the young people doing the laboring. The young people

themselves saw it otherwise. To them, it was a chance to learn meditation, and

to practice it in a community with others who at least looked like they knew

what they were doing. More importantly, a genuine meditation master lived at the

centre where all the cleaning, sweeping, cooking, sewing and painting took

place—an old man of Japanese descent, who had been practicing Zen for 50 years. A book of his teachings had been published,

drawn from weekly talks to students, and a wide spectrum of readers had praised

it as helpful. This slim volume, attractively designed, felt like a kind of

wisdom text. It bore a picture of the master across the entire back cover; he

was shown in work robes, unshaven, wearing a handsome, enigmatic, half-smile. It

felt that in opening the pages you were opening more than a book. Reading even a

little bit seemed to be associating yourself with something and someone

positive. The group of people who joined the master

for meditation morning and afternoon had grown, and was now well beyond the

capacity of the temple in Japantown where he’d begun his American career a

decade earlier. The demographic had also shifted—from a congregation of

middle-aged Japanese adults wanting a temple priest to lead ceremonies and do

seasonal rituals, to a collection of mostly young, mostly white Westerners (some

of them unkempt in the style of hippies) wanting a living, breathing Zen master

to guide them to satori.

Eventually the younger group prevailed.

They found a building several dangerous neighborhoods removed from Japantown,

and bought it. Designed and built many years earlier by Julia Morgan—an

architectural treasure—it nevertheless required enormous work to clean and

renovate, especially as it was to house a meditation hall, a private apartment

for the master and his wife, and private rooms, both singles and doubles, for

some 50 rent-paying residents. This work had been largely, but not completely,

accomplished by the time I arrived. I hadn’t called ahead, nor written. I’d

simply hitch-hiked down from college in Oregon, thinking to use the couple weeks

of Christmas vacation for spiritual advancement. They didn’t let me in right

away. I mean I was allowed in the front door, after a frank appraisal from the

fellow who opened it, but told to go wait on a bench in an alcove while they

checked about space in the Men’s Dorm. There wasn’t any. The people in the front

office put in a couple calls, and found me accommodation in a flat a few houses

down the hill. It was communally rented by a Zen pair and some other friends.

From there, it turned out, I could easily attend the 5 a.m. sitting at the

centre, and follow the schedule of devotions that developed from that: walking

meditation, more sitting, a service of bowing and chanting. Afternoon meditation

was also open; meals were not. Not being present for these, I missed the work

meetings that followed breakfast and lunch.

Two days later though, I took

my sleeping bag, and my backpack of possessions to the Men’s Dorm, as a space

had opened up. I was one of six who slept in the room, each of us on a single

tatami mat arranged around the perimeter of the carpeted space, with a low table

in the middle, for books, glasses, clocks…This room was in the basement, though

given the way the building had been set into the hill, we were actually at

street level. Out one window, past the iron bars that protected it, was a few

feet of ivy-covered yard, a hip-high fence, then the sidewalk, and parked cars.

It wasn’t much of a view, but we weren’t there for the view. The Men’s Dorm was

conveniently next to a men’s bathroom and then down a few stairs, the entrance

to the zendo, the meditation hall. For most of us bunking there, that was the

point. There was almost no obstruction to our getting into the meditation hall.

It is true that we paid a daily fee to be there, but we would have paid for a roof over our heads anywhere decent, the crash-pad ethics of San Francisco notwithstanding. The meals were also good, and plentiful. It is true that between these meals and the periods of meditation, we worked. It was practical work, and no bones were made about it. Chinese monks had started the tradition, centuries ago. On our daily schedule, it was called “Work Period”. Still, it was regarded as part of Zen activity, the spiritual practice with which we filled our days; and everyone—including the master himself, on certain occasions—did it.

Administrative staff might find

exemptions, but only because they were otherwise employed. Working. It was plain old work, but we did not play

the radio as we scrubbed decades of grime from the stairwell walls. We did not

flick cigarette butts around as we cleaned up painting equipment. We did not

cat-call, whistle, or stare if we were weeding, or unloading vehicles, or

sweeping the long stretches of inner-city sidewalk that bordered our building.

We were supposed to put our whole minds on what we were doing—“to become one

with our activity”—and as part of that, we were also not supposed to talk

unnecessarily. This latter advice was challenging. As a group who’d assembled

itself from all over, drawn together by the esoteric practice of meditation, we

were curious about one another.

The Work Leader embodied this problem

personally. He was a serious fellow, and his job—one of the

traditional six big ones in a Zen

temple—demanded attention both detailed and panoramic. He worked with lists,

went to meetings, kept a number of interlocking projects moving forward, and

dealt with an unpredictable work force, a variable crew of temporary, unknown

quantities, like myself. If he had time as he floated from project to project,

the Work Leader would join in for a while. He almost always participated at the

set-up phase, and he made sure that things were finished well, overseeing

clean-up and storage of tools. Working alongside you, he might suddenly blurt a

question about where you were from, or if you were in school, and if you were,

what you might be studying—as though there were no discouragement of such talk.

When the work was hard, he did not hide (verbally) that he too suffered doing it

with you. He didn’t pretend to be unfazed helping to lift something heavy, nor

did he disguise pleasure at a task skillfully or thoroughly done. His smile lit

up his face, and there was real delight in his laughter, which came easily,

though it often began silently. Still, he conveyed a sense of strictness. You

did not want to be late for work meeting, nor to cross him in other ways. A

decision, once he had taken it, was not to be questioned, even if it seemed

inefficient. The person who had the most obvious effect

on our Work Leader was the master himself. Contact between them was not rare.

Master Suzuki—Suzuki-roshi—would be consulted about aspects of a project: a

color choice perhaps, or the placement of things, especially, if those things

were rocks. Large stones, trucked up from the centre’s rural monastery, had been

arranged in the interior courtyard, as the basis for a garden there. Such work

keenly interested Suzuki-roshi, and he participated to the degree that his time

and health allowed. At the very least he watched, as the old technology—winches,

skids, blocks, tackles, levers, and raw human muscle—brought the work slowly

forward.

I saw how it took a full morning once to

get a bench-sized sparkling piece of granite from the back of the flat-bed truck

up the centre’s front stairs, and into the door. The afternoon of that day was

given over to moving the stone across the polished red floor of the front hall.

There it rested for a day, as did the stone crew, while plans were made about

how best to move it from where it rested, to its final position in the

courtyard. Considerations included causing the least possible damage to the

interior floor, the window frames, and the exterior cement. During these

discussions, our Work Leader—Steve, he was called—was fully engaged. He, other

earlier Work Leaders, and several types who thought of themselves as rock-work

specialists, went over every aspect of the project. They did this with

Suzuki-roshi, and around him, and in the course of the talk, they frequently

praised the rock. Suzuki-roshi had picked it out from a creek-bed in the

mountains.

During the talking and the working, they

signalled deference to Suzuki-roshi. It is not easy to say exactly how they did

this, but to an outsider, even a novice like myself, it was clearly so. Part of

it seemed to be in the way they spoke, in how they moved, and where they

positioned themselves in relation to him. I was seeing a number of much larger

men—Roshi was not tall—managing through nearness, distance, and even the

altitude from which they addressed him, to communicate respect, as well as

whatever practical matter was at hand. This obviously included humor. In

photographs of similar work discussions, the crew, including Steve, wore

expressions running from serious to adoring. Some are laughing; one or two faces

glow the way a parent’s does, looking at a new-born, or watching a child’s piano

recital.

I too experienced a range of emotions the

first time I actually laid eyes on Suzuki-roshi. I had come in the front

door—late, it was soon made clear to me—for the Saturday morning lecture. I must

have still been lodged down the street, and not have understood the protocol,

the crucial importance of being at least ten minutes early for talks. In any

case, Suzuki-roshi came down the hall, moving in a stately way toward the

entrance to the Buddha Hall. He was trailed a respectful few paces by an

attendant carrying incense. Whoever opened the front door to let me in also held

me back. Apparently, one did not scurry in at the last minute in front of the

master. One stood where one was and was observed to be late. I also learned

later that the crescendo of temple bells resounding in the building, seeming to

come from nowhere, was the musical accompaniment just for the entry of the

speaker.

Perched amid the dozens of street shoes and

sandals and flip-flops that had been (mindfully) kicked off before going into

the Buddha Hall, restrained there like a spectator at a golf tournament, I

finally saw the roshi. He transfixed me as he came along. paused at the

entryway, turned, removed his slippers, turned again and continued on toward the

altar. Forcibly halted, I wished first that a giant mud puddle would appear in

the floor, so that I could lay myself down in it and have him walk over me;

simultaneously—with no gap at all—it was utterly clear that the man I wished to

serve so, to offer myself to, to adore, was made of iron, and didn’t need

anything from anyone, certainly not from me.

Of the talk itself, once everyone had

settled—I in some wall-hugging, last-row space— I remember few, if any, of the

words. It felt like Roshi knew where he wanted to go in the lecture, but his

pace was slow, with many pauses and much amusement. He

laughed almost privately, almost silently. He spoke a heavily accented English

that I recognized from out of the mouths of many of his senior students. During

Roshi’s pauses, it seemed you could watch thoughts moving through his mind. His

expression would change, then change again, and he even looked surprised

sometimes at what had occurred to him. Then he would say something. This was

hypnotic; we were hanging on every word, yet it seemed only to be his normal

manner of expression—innocent, and undefended. I was not part of the stone crew. That was

a restricted group, and initiation came at the monastery, where the creeks

supplied an endless selection of rocks, from gravel to boulders. These were

refreshed seasonally, with storms and occasional winter floods. There, I learned

later, retaining walls were built of stone, and stairs, pathways, some cabins,

and even the four high sides of an industrial kitchen. We passed this kitchen

several times daily on the way to the meditation hall, and it amazed some of us

how the walls were square to one another, right-angled, as if rocks had been

made to go around a corner. But back here in the city, especially

interior to a building made beautiful in another time, the rocks were

decorative. This is not to say that placement of them was any less earnest, or

less consequential. The rocks were core elements

in a garden into which guests would be invited—a place people would spend time,

have conversations, take pictures. A picture of Suzuki-roshi gesturing showed

that several of his fingers had been broken. Word was, moving rocks. The back stairs ran from the garbage cans

and paint sink and delivery entrance at street level, up some four floors to a

roof-top herb garden and laundry area, with spectacular views of east- and

south- San Francisco. A stocky fellow called Dan and I had spent most of a week

back there, washing the walls with TSP, priming them, and getting parts of them

repainted. We were now up near the top, where the stairwell gave onto the roof,

and parts of these walls were unreachable without scaffolding. Steve had

supervised our makeshift construction of planks and ladders, and had tested it

himself, before letting either of us—and only one at a time—clamber up. Several

passersby on their way to the roof had admired our work as they squeezed past,

and commented, perhaps with a tinge of flirtation, at our bravery. So Dan and I

were a little miffed to be pulled off this job at the point where we finally had

space over our heads, and light, and a bit of appreciation. It turned out though

that we were given a plum assignment.

At the morning work meeting, Steve took us

aside to say that Dan and I would be painting the interior of the bedroom closet

in the modest suite of rooms where Suzuki-roshi lived with his wife. The Suzukis

would be out for the day, because of an obligation with the Japanese

congregation. They had agreed to leave their closet empty until their return

late afternoon. A first coat of paint had been put on some weeks earlier, but

hastily. As soon as the apartment was empty, Steve told us, we were to go in, set

up, and do whatever touch-up work was necessary. If there wasn’t much,

Steve would

put a heater in the closet at lunch, and in the early afternoon we’d put on a

final coat of paint. He wanted us done and out by the time the Suzukis returned.

He also wanted to have as much time as possible to air the place out.

We assembled our materials: drop-cloths,

masking tape, a couple small buckets of paint (bone white) and brushes of

various sizes. These we took up to the hallway outside the Suzuki’s rooms, and

stored them as neatly as we could. Then we had to wait, and the waiting was hard

on Steve. He really wanted to get us started, but there was no way anything could

be done until the Suzukis left. He didn’t want to assign us to other work,

because we’d just have to be pulled off it the moment their little flat—living

room, bedroom, kitchen and bath was free. It gnawed at Steve to have us idle, but

he finally gave us a break. We could get a hot drink in the small kitchen, he

said; we should be findable. We were to wait in the room where newspapers were

read, informally (but universally) called the Flop Room. Much like the Men’s Dorm, the Flop Room featured a low table in the middle. The

floor was covered in carpet shaggier than the one we had in the dorm, and

instead of tatami mats around the walls, this room featured a comfortable couch

three seats wide, a couple armchairs, and a selection of large pillows. There

were habitués, but no one seemed to stay there very long. People got a tea or

coffee, read some of the paper, maybe snacked, and went. One or two mothers

played from time to time with infants on the interesting rug, or nursed them

among the pillows. As Guest Students, Dan and I had had neither time nor

occasion to be in there. Feeling like trespassers, we knelt at the table and

waited for Steve to collect us, which he soon enough did. Down

the hall, we could see the Suzukis being attended as they went out the front

door to a waiting car. We all paused to watch, before mounting to the next

floor.

Dan and I had never even been in the

Suzuki’s wing of the building; there was no reason we would have. Next to their

private apartment was a larger room with a separate entrance, Steve said, pointing

to it, in which Roshi did interviews and met the staff for morning tea. Further

down—this wing ran three or four rooms on each side—were offices, and the

residence rooms of temple staff, whose titles I did not recognize when Steve

mentioned them. At the far end of the hall, glass doors

opened to a fire escape, and sunlight slanted in through these. As a structure,

the whole building held the corner it sat on well, being large and dignified,

even imposing. But the interior, with its courtyards, arches, and many large

windows, felt open, penetrated by light on all sides, no matter which floor you

were on, no matter which part. Julia Morgan had designed it as a residence hall;

a respectable address for young Jewish women in need of a safe place to be while

in San Francisco. Steve knocked reflexively on the door to the

Suzuki’s flat, then opened it and stepped over a raised threshold. Whereas he

frequently pointed things out to us about the building, here he was the

opposite. Shoji-screens stood in the rooms, forming a kind of corridor for us to

go along with our materials; but even if they hadn’t, it felt like Steve was

unfurling some sort of cape, to block our possibly roving eyes, and to guide us

without distraction to the walk-in closet where our work lay. He stayed with us

as we spread canvas drop-cloths, and taped the edges of the baseboards and trim.

He inspected the corners carefully and pointed out where we should concentrate.

After we’d carried in the paint, he went off—to see about a space heater, he

said, and extension cords.

Dan and I finished our morning work in time

to set the brushes to soak, and to change out of paint-clothes for the mid-day

recitation, the one before lunch. This was usually sparsely attended; even we

Guest Students didn’t often get there, though we were to follow the temple

schedule as completely as possible. Work ranked higher than this particular

ceremony of bowing and chanting. If, by getting something done we went overtime

a little, and didn’t make it to the Buddha Hall, no one cared, not even

Steve.

This was explicitly not so for the afternoon meditation period. Steve ensured that

we stopped whatever we were doing early enough to clean our materials, clean

ourselves, and rest a little before attending that sitting.

Back to the closet after lunch we took more

paint, and more serious painting equipment. It made Steve edgy. In the cramped

space we now had a folding ladder, a five-gallon bucket and another small can of

paint, rollers, trays, brushes, and a wheezing heater on drop cloths covered

with electric cables. Given that neither Dan nor I was small, there was no room

in the closet for Steve as well. He would have to just leave us to it—either that,

or paint the closet himself. He reminded us that we were in the roshi’s

quarters, and that nothing should go wrong. He finally laughed a little as he

said this, because it was obviously a set-up for disaster.

As usual, Dan and I had both eaten as much

lunch as we felt we could get away with. Fumes from the paint rose and collected

in the closet, and the heater intensified them. We were wearing painting gear

over our regular clothes and Dan soon looked very red in the face and neck; I

felt I must too. Moving in an enforced slow motion, we painted the closet. Steve

seemed relieved when at last we rolled paint onto the lowest section of the

walls, and set our tools in the trays.

We were standing thus, Dan and I in the

closet, Steve just outside it, talking over the order of our retreat, when the

door to the apartment opened, and the Suzukis came in, unexpectedly early. Steve

went to them, leaving Dan and me standing there. We stood there more than a

little while, until Steve returned, ruddy-faced and smiling, with the Suzukis,

Roshi leading. He wore glasses—not the kind of double-monocles he’d put on and

taken off several times during his talk. Those had been on a thin chain around

his neck. He’d fished them from deep in a robe sleeve before beginning, and

returned them there afterward. Now he was wearing more conventional street

frames, dull gray-brown along the top and clear below. Perhaps I noticed his

glasses because I too wear them, and mine were presently flecked with paint. It

felt as though Suzuki-roshi was looking at the dozens of tiny spots on my

glasses as he smiled in at Dan and me. His eyes traveled up to my hair and his

smile broadened. It wasn’t quite a military inspection, but I watched him look

at my overalls, my shoes, and then at the drop-cloths. He turned to Steve and they

murmured with Mrs. Suzuki. “Mmmmmm”—mostly approving sounds, with some

interrogative tones mixed in. Some surprise.

The Suzukis went out of our sight, and

Steve

returned to the discussion of how we would get everything out of there. He

reached in himself for the ladder, which he carried alone out of the apartment.

Dan and I poured the remaining paint from the trays back into the five-gallon

container, and divided up what we had to carry. I was about to leave with the

big container in one hand, and the trays and rollers balanced in the other, when

Suzuki-roshi reappeared at the closet door, indicating we should wait. He had a

newspaper in his hand, and he bent to spread open a section on the floor of his

bedroom. He backed up a couple steps, spread open another section, and then

repeated this. He motioned that we could now come ahead. Stepping gingerly on

the paper I went toward him, as he backed up, bent down, and spread open more

newspaper. The sources of mortification were multiple. I couldn’t imagine how we’d been so

idiotic as not to think we might track paint through his apartment. We hadn’t

exactly painted ourselves into a corner; we’d painted ourselves into a closet we

couldn’t get out of. Still worse was the prolonged choreography of our

departure—the picture of this older man, bending down in front of me as I

clunked forward. The master, my hero, backing away at my dumb Western feet,

gesturing as if scattering rose petals, bowing and scraping, making a mockery of

my mindfulness, but cheerfully. Smiling, even chuckling as he backed away and

bent over in front of me. It is an image that embarrasses me to the present

moment. This one. |