(Note: click on tiny images to display additional photos.)

For a time in my twenties I took copious notes as sort of a meditative practice. So during the six weeks my husband and I spent at San Francisco Zen Center following the death of Chris Pirsig, I poured details of the experience into a small notebook. Immediately afterward, in January 1980, there was time to compile the notes into a handwritten chronological account, later typed onto a personal computer. I never had plans for sharing it, but after becoming acquainted with the rich archives of cuke.com, edited it to offer as part of the historical record in the fall of 2022. I am grateful to Cuke Managing Director Peter Ford for thorough copy editing and David Chadwick for fact checking.

Thursday, November 22, 1979

As our flight from London landed on Thanksgiving Day at JFK in New York it was overcast. We saw nothing of the city but enjoyed the familiarity of Americanese language as the flight attendant reminded us in a New York accent that at customs we would have to declare “plants, vegetables, seeds, marijuana and the like.” He recommended taking public transportation and warned against “getting ripped off by unmetered taxis.” Then he thanked us for flying Trans World Airlines because “we need your money.”

And then there was the generosity of the female attendant when I asked to borrow a dime to call San Francisco Zen Center while we waited for luggage, because we hadn’t yet changed currency. She gave me a dime and said to keep it.

The reason for calling was to try to get more information and to arrange to be picked up at the San Francisco airport. I spoke with someone who sounded about my age. Her name was Meg Porter and she spoke with a clear, calm and intelligent voice. She answered each question without elaboration, giving exactly what was asked for and no more. Chris’s funeral would be in three days, on the coming Sunday afternoon. Katagiri-roshi ✽Katagiri was abbot of the Minnesota Zen Meditation Center, where Bob and Nancy Pirsig had been founders and Chris and Ted had studied. would arrive from Minneapolis on Saturday afternoon. Nancy and Ted ✽Chris's mother and brother would return Saturday night from his home in Seattle. They had come to San Francisco immediately upon hearing the news, earlier in the week. They had gone through Chris’s things and transferred ownership of his car to Ted. During Nancy’s one full day there, there had been a small press conference involving three radio and one TV station. Nancy had made a “plea for information,” Meg said, and offered a reward “by the family.” Bob and I had heard from Maynard ✽Bob’s father about a reward offer but thought it came from Zen Center.

A vigil had been held at the coroner’s office, Meg said. The person who could tell us most about it would be Reb Anderson. Chris’s body, Meg believed, had by now left the coroner for cremation, which would take place tomorrow, Friday.

Reb Anderson was a name Bob knew. He was the chief priest at Zen Center’s downtown City Center, and Chris had admired and mentioned him often. Bob had met him once at Minnesota Zen Meditation Center but hadn’t spoken with him.

When I asked Meg what Zen Center was doing in response to the incident, she said she thought things were being done “in a quiet way.” Many people had come to a memorial service the night of the murder, but since then, “we’ve been quiet. There’s very little response that we can make.”

I then came to some of the more awkward questions. I asked if Nancy’s boyfriend Martin was there, and Meg said no, just a cousin, Judy. Bob thought she might be the daughter of Nancy’s sister, Geraldine.

Finally I asked about the murder itself. We knew almost nothing. The report we’d had was that Chris had died with friends, but now Meg said he was dead when he was found. “No one heard him cry out.” There had been a single wound. It had happened on Saturday night, November 17, at 7:45 pm. I got off the phone and ran to catch the plane to San Francisco.

This time the flight attendant was a joke-cracking Chicagoan: “Anyone caught smoking during the no-smoking sign will be asked to leave the plane.”

After we took off I told Bob about the phone call. He focused mainly on the disappointing news that Chris had died alone after all, and that his body had not been at Zen Center, as we’d imagined.

This plane was more crowded, but there were three seats for the two of us. As it was Thanksgiving we’d been served turkey on the flight to New York. Now we had a second turkey dinner, better than the one baked in London. There was a long twilight over the clouds, and then the movie came on. Since I had gotten more sleep on the earlier leg, I convinced Bob to lie down while I tried not to watch the film.

I was holding Bob’ head on my lap when Chris came to visit us. I imagined he sat just behind us and across the aisle, sort of looking at Bob over my shoulder. There was a sense of admonition as though he were reminding me to honor and be worthy of his father. We had been talking before Bob fell asleep about going to the mortuary to get a last look at Chris’s body before it was cremated. Bob asked me to call the morgue in the morning and say that the father wants a last look at his son. “I don’t care if the autopsy has been done. You know, they slit the chest cavity open and peel the flesh back to examine for the knife wound and everything. You tell them I don’t care. I think it’s something I should do.” So Chris’s visit had to do with this proposal. When Bob woke up he mused about the Tibetan Book of the Dead, and on what death is. Where did Chris really go? And he decided, still lying on my lap, not to go to the mortuary after all, “because that isn’t Chris, that’s just a piece of meat.” He talked for a long time, wondering out loud, and I told him about Chris’s “visit.”

“He told me on no uncertain terms to take care of your aching heart,” I said. Bob cried again and we hugged each other, and that was the end of his nearly continuous four-day crying spell. From then on he only cried his usual way, little quick spells. Flying along in the dark, we felt close. He told me Chris had a dharma successor after all: me. In a way Bob didn’t understand, he said, I was a form of Chris’s reincarnation.

We had been living aboard our sailboat for three years, most recently in Falmouth, England, where Bob was working on his second book, Lila. He’d written five chapters out of 30, and I was trying to write a novel. We’d been married about a year. It was on a call from a pay phone to Bob’s father, Maynard, in Minneapolis, that we had learned that Chris had been killed. A few days later a telegram arrived from Richard Baker, Zen Center’s abbot, saying a funeral would be held at City Center. Katagiri-roshi of Minnesota Zen Meditation Center and Baker would perform the ceremony jointly. Katagiri had been Chris’s teacher before he left Minneapolis.

We had never met Baker before. He had written in his telegram that it was important to Bob’s family and it was important to the Zen community, and “I know as much as it is possible that it is important to Chris for you to be here” for the funeral. We were eager to speak with Baker soon to finally learn everything about the terrible thing that had happened.

At 7 pm Pacific Time we at last circled over a city of lights, having seen almost nothing of the earth since England. It felt strange that this could be San Francisco, California. We were better rested and not too exhausted, and quite excited.

As we walked to the airport gate we spotted a lone figure with a shaved head and Bob whispered, “He looks just like Chris!” The man, who had droopy eyes and a head shaped like a perfect egg, introduced himself as John Bailes. In a soft voice he said he was Baker-roshi’s assistant—one of many, it turned out, rotating through the many Zen Center jobs. Waiting for luggage we made small talk about ocean sailing. We had recently crossed from the US to England in our boat, and John knew a sailor who had drowned in the Atlantic. John was originally from New York. Bob described him later as an eastern patrician. I wondered if he were Jewish and acting like an eastern patrician while completely made over into Zen style: powder-soft voice, quiet mannerisms, erect posture with steady bearing of head and body, and, like Meg on the phone, absolutely no unnecessary speech.

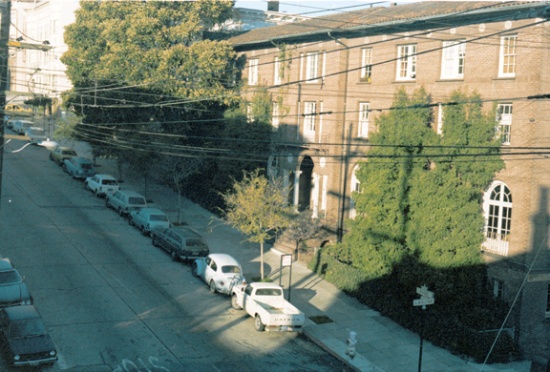

We got in John’s car and headed into the city. He said Baker was at Tassajara because the monastic training period was going on, but that he would return to San Francisco the next day. In response to a question John said that after Chris died Saturday night, a bell called the densho bell was struck a special number of times—over 100, both at City Center and out at Tassajara—and there had been a service. He said a story had run in the New York Times. He deferred other questions to Reb Anderson or Zen Center President Ed Sattizahn, another new name to us. Bob didn’t press John with questions, and though I had a million, I kept quiet. Soon we pulled off Highway 101 and came to a stop a couple of blocks away on Page Street in front of the Zen center.

From the moment we arrived, the neighborhood gave me the chills. The two- and three-story buildings climbing the hill from the expressway did not look charming despite their Victorian architecture. Sidewalks were dimly lit, and nobody was out on the damp, dark streets. City Center itself, officially Beginner’s Mind Temple, presented a somber old brick institutional facade.

In addition to City Center, and meditation centers at Green Gulch and Tassajara, San Francisco Zen Center owned Greens Restaurant, recently opened across town. We knew that in the Page Street neighborhood Zen Center operated a bakery, where Chris had worked, and a neighborhood grocery store, Green Gulch Green Grocer, offering baked goods and Green Gulch farm products. But none of these were visible to us on that dark November night.

Across the street from City Center we were led to a building called the Guest House, and nearby John pointed out in a little park a fantastic mural of Krishna, the Hindu deity. But the park was just an empty house lot and was unlit and dangerous looking. The Guest House door swung open onto a cavernous hall and drab stairway, where we were supposed to go.

Inside was better however. John led us upstairs into a front room which was truly beautiful. It had high ceilings, a fireplace and a bay window, a big comfortable stuffed chair and sofa overhung by a chandelier, a desk and bookshelves, a large double bed in an alcove, and woven gold wallpaper. We were later told the room had been decorated before Zen Center owned the place, but the Zen students added a Japanese calligraphy over the mantle, Chinese sandalwood soap in the private bathroom, and fresh flowers everywhere. On a lovely square teak coffee table in the center of the room sat an oval basket of fruit and nuts, complete with knife, nutcracker and paper napkins. While we exclaimed our appreciation, John lit a fire, then sliced us each a piece of exquisitely ripe persimmon.

Responsible for this welcome, it turned out, was none other than Meg Porter, the person I’d spoken with on the phone. Meg soon appeared with pumpkin pie and tea, and she would have served us dinner brought over from Zen Center, too, if we had been hungry.

Meg was a lay priest Zen Center had assigned to be in charge of its Guest House. ✽She wasn’t a lay priest. There was no such thing. She was a student in charge of the Guest House. - DC She was 38, and I thought she resembled First Lady Rosalind Carter, or an old-fashioned doll. She dressed in skirts and talked in a soft, almost whispered voice. Her manner seemed reserved.

She handed Bob a telegram from an acquaintance who had learned we were coming—a filmmaker interested in making a movie of Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance (ZMM). It expressed condolences and made Bob’s eyes well up. “I get this way mainly when other people express their sympathy,” he said. Afterward Bob and I reflected that one thing none of the Zen students ever expressed was sympathy. The other thing nobody said was, “I’m glad you are here.” But as we arrived that night, we thought they were; it seemed like they would be.

Meg asked if we wanted to see Reb and Ed, and Bob replied, “Sure!” While we all waited for them he began telling stories. He told his tiger hunt story, describing the India of 1950, and launched into lots of other descriptive information about travels, such as Koreans he met in the army in the 1940s smelling different because they ate fish. “They smelled like someone had pissed in an old boot.” I thought this was funny and Bob told most of the story while looking at me, while Meg and John sat to each side, pouring tea beautifully, but neither laughed heartily. Meg had a way, when Bob delivered a line, of puffing up her face and turning it away to look at me before chuckling quietly.

Then suddenly, there was Reb, the Tanto, or senior priest of City Center. We didn’t hear him come, but Meg or John suddenly said, “Here’s Reb,” and a tall figure wearing black robes glided into the room as silently as an owl. His head was shaved, and his skull had a knob shape on the back. He seemed to be in his 30s, with a long, thin baby face and a pushed-in mouth that had a kind of Buddha’s smile playing on cherubic lips. He had a strong jaw and his body looked strong, tough, wiry. His expression was calm, but alert and attentive, and his shining black eyes had no limits. The rest of us were lounging on stuffed furniture, but he took a straight-back canvas folding chair. Like the others Reb had a quiet voice with no chatter. But his, quiet though it was, somehow seemed to come from somewhere in the earth, as though he carried great powers.

Among the first things that happened was that Bob told Reb how often Chris had spoken of him. Reb said, “He was like a younger brother.” Bob said he understood Reb was from Minnesota, and he said yes, from Minneapolis, though part of his life had been spent in Hopkins. He got talking about his name.

“My real name is Harold,” he said, “after my father. He nicknamed me thinking ‘Reb Anderson’ sounded like a good name for a football player.”

Then Ed Sattizahn arrived. Ed seemed about the same age as Reb, but instead of medieval monastic costuming he wore regular clothes and a “presidential” haircut. He had a relaxed, easy smile and beaver teeth, and seemed like a person of good sense. After the round of handshakes, he took another canvas chair beside Reb. The conversation drifted to funny stories about the early sesshins, days of extended meditation, in Minneapolis before Minnesota Zen Mediation Center was well established. At the beginning of the first sesshin, after Katagiri had just arrived and nobody knew anything about Zen practice, one student told everyone that they could come and go as they wished all day long throughout the zazen periods. So they all did—and Katagiri did not say one word. No one realized it was wrong till the next sesshin, when he gave explicit instructions that stillness was expected.

Pretty soon John excused himself and left, and then Bob asked for details about the assault on Chris Saturday night. This was the first time we realized that apart from a very few people, nobody knew there had been witnesses. Meg asked if she should leave, but Ed and Reb said it would be all right to stay. Ed spoke with clear, calm, centered speech about what Zen Center had been told. He leaned forward just slightly on the armrests, looking most of the time at Bob but glancing occasionally at me. He said Chris had been walking to a friend’s house on Saturday night when, on the corner of Haight and Octavia ✽about two blocks away from the center, a car pulled up and two Black guys got out. At that point two other guys were walking by, one Black and one White, both “speed freaks” and quite young and on the lam for parole violations and possibly crimes. “They knew all about this kind of robbery,” Ed said. “They do the same things themselves every day.” So they wisecracked as they went by.

After hearing something, they looked back. Perhaps it was Chris yelling or crying; they thought maybe he had been hit. Then the first guys stabbed him, got back in the car and drove off.

The witnesses called to Chris, “Do you live around here?” and he said, “No.” Then they decided they better leave. A man walking his dog was coming by, they said, and they figured he’d take care of Chris.

This account had come to Zen Center’s attention the next day, when the two witnesses visited an acquaintance who was connected to Zen Center. They remarked, “Hey, we saw a murder last night!” This person got them to talk to Zen Center. “We paid for a room and food for the witnesses,” said Ed, referring either to Zen Center or the streetwise Zen students who interviewed and kept them there so they wouldn’t disappear; I think it may have been in the Tenderloin.

The killers, however, are unknown—no names, no description. They are believed to be small-timers from one of the housing projects in the area, but not, Reb thought, from the nearby one up the hill, because Zen Center has contacts there. Ed pinned the partial success in information-gathering to Issan Tommy Dorsey, a senior monk whom Ed or Reb described as a former drag queen, and Peter Coyote, an actor. Both are Zen students with long histories on the streets of San Francisco. Ed said the police could hardly believe it when Zen Center, of all sources, furnished eyewitnesses and a description of the getaway car. They are hopeful about making arrests. One of the cops heading the case is Black. Ed wondered if we could help pay for the support of the witnesses and Bob said yes, he was eager to pay for anything. He also asked if more reward money would help, but Ed told us the police said no.

(Peter Coyote never much discussed the case with us, but much later he did say that at first Zen Center had had a no-holds-barred spending policy on investigating the murder. “Tell me when you hit $5,000,” was what treasurer Steve Weintraub told Peter when he asked about spending limits on pursuing the case. In the end, though, Zen Center didn’t have to spend anything, as the case fell apart. Small expenses related to the witnesses were covered by us.)

At one point I asked what news coverage there had been, but Ed and Reb didn’t know. We knew that the San Francisco papers had run the story on the front page. The press conference had been called for broadcast media as a way of fending off a press invasion that might disrupt practice at Zen Center. Beyond that, no one knew.

Then Bob talked about Chris. He kept his eyes on Ed but I felt he spoke mostly to Reb. Bob told the story of Chris’s adolescence, beginning, “I don’t know if he ever told you he tried twice to commit suicide?” and glancing quickly at Reb, who shook his head. Bob said Chris’s troubled years took a decided turn for the better after Bob got him to sit with Katagiri, and he praised San Francisco Zen Center for the four years they had given Chris. He said the Zen practice he was learning had saved him.

Reb told a few stories about Chris’s rough start at Zen Center. Sometimes during the conversation it seemed Reb’s eyes grew wet, but it was hard to tell. Never did Reb seem to be trying to get anything.

“Chris tended to sleep a lot in the morning,” he said of Chris’s first days in California. “When we sent him to work at Zen Center’s farm at Green Gulch I told them, ‘Here comes a good man, but make sure he gets up for zazen or he’s shot for the whole day.’” So people would appear at his door every morning and drag him out of bed.

Reb said soon after Chris had first arrived he came up to him and said—and Reb imitated Chris’s super-serious expression— “I want to be a monk!” We all laughed picturing this. Reb said he told Chris, “This takes time.”

He also let slip an anecdote about bailing Chris out of jail once on a parking ticket rap. He didn’t elaborate and Bob didn’t ask, but we laughed again.

Then Bob expressed gratitude about how far Chris had progressed. He had me tell a story about a dream I’d had of Chris walking across a dewy lawn. He was at the family’s house in St. Paul, walking as though in a trance, and then drifting away without leaving any footprints in the dew.

Then Bob talked about what had happened on the plane, and how he had read the Tibetan Book of the Dead and had been thinking about what happened to Chris when he died, that he wasn’t just a “piece of meat,” and that Bob had looked at me on the plane and thought how some of him had been transferred to me.

This was getting pretty weird, but Ed and Reb seemed to ride right along with it. And to my surprise Reb then told his own story. He said that when they found Chris on the street, his face had an expression of peace, “like a baby.” And a few days later Reb saw a vision of him.

“I usually like to lie down after breakfast. Not for a real sleep, but just for a short while. And the other day, when not quite asleep, I saw Chris’s face, except it wasn’t his usual face. It was like he was much, much younger, and it was a rounder kind of face. Like a baby.” Reb spoke with a little wonder in his voice but without great excitement, as though his experience was a normal occurrence.

The conversation moved on to the Sunday funeral. Reb said some of the newer students were having difficulty “knowing how to grieve.” Murayama Sensei was here and might be involved in the service. We realized this was a Japanese priest we knew as Shoki from a fall sesshin we had attended in Minneapolis. Reb said he went jogging every day with him. Sometimes they jumped into the ocean for a swim, even in November. Suzuki-roshi’s widow, Mitsu Suzuki, affectionately dubbed Okusan ✽Japanese for wife – DC, who lived in City Center, had heard about this feat and playfully said it showed that Reb was a “real Zen master!”

At last Reb said it was late and time to go, and we all got to our feet. I felt grateful and started hugging Ed, who was closest, while Bob shook hands with Reb, and then vice versa.

Then Reb suddenly turned to me saying, “So you’re Chris now?!” and he looked about 20 fathoms through me at a range of three feet. Taller than me, he also seemed so powerful he could atomize anything on the spot. I tried to hang onto the roller-coaster effect.

“Yes,” I said.

“Pretty strong!” He smiled, and then he added, “You sort of look like him.” And then he glided away.

That night we asked Meg how safe it was to walk around the neighborhood. She said daytime was okay, but even then it was better to go by twos. At night, never go anywhere unless you have to. A notice in the guest room advised against meandering or parking very far away, and a map showed the safe area was limited to within one block from Zen Center at Page and Laguna.

November 23, 1979

I awoke at 4:00 am hearing Bob crying and the sound of the street. Occasional cars would pass. Now and then there would be a police siren in the distance. And from very far away a foghorn.

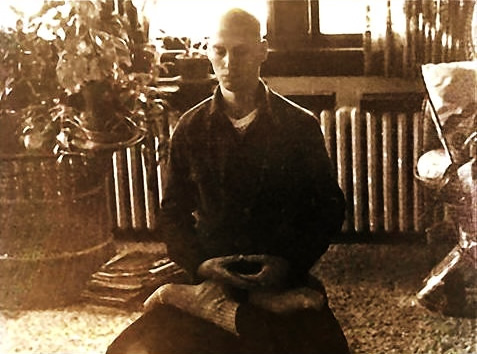

Photo by Wendy Pirsig, December 1979.

We were still full of good feelings from Reb and expectations. Quoting Paul Reps’ book Zen Flesh Zen Bones, Bob recalled, “There’s a Zen story that says, ‘What is the greatest happiness in life?’ Answer: ‘Father dies, son dies, grandson dies.’ That is the answer because that is the natural order of things. It explains what we feel when the order is broken. Katagiri will be taking this as hard as I am. Chris would have been his dharma successor, I’m sure... Oh, it’s so good he did so well at Zen Center, that Katagiri singled him out that way...”

The final sentence of Richard Baker’s telegram had been, “Your son was a very fine courageous young man.” Bob wondered at Baker’s use of the word courageous. It struck him wrong. “It’s just not a word you’d use to describe Chris,” he said. Was it because he had fought his attackers? We knew so little still, and hoped Baker soon would tell us.

“His years at the Zen Center were good,” Bob recalled. “He was known at all the centers. He got to be part of Tassajara. He got to be up there during an exciting time, too, when they had the fires...”

Before we knew we were going to San Francisco, Bob had sent a condolence letter to Zen Center that began, “I have just learned of Christopher’s death and am in great pain,” and then went on to say how happy a life Zen Center had made for Chris. He said that zazen was the center of Chris’ life, as they were aware, that he had understood how to work through pain, that you can’t go around it. He encouraged them to meet “all the Christophers who appear at your door” with the same spirit as they met Chris. He said we, meaning the two of us, will honor him by continuing to follow the Buddha way as best we can.

Talking with me, Bob said that perhaps we should join the Zen Center now. Sail the boat to San Francisco via the Panama Canal. Maybe Ted would join us.

“I’m glad I told Chris I supported his entering the priesthood. He always wanted to win my approval so much. I’m glad I visited him here. He was so proud, showing me around. And everyone was peeking around corners and watching out windows when I was with him that day. He said people had asked before, ‘Where’s your father? Why doesn’t he come visit you here?’ and he would say, ‘Don’t worry. He’ll be here.’ And then I came…”

Before we left England Bob had had me copy a passage from our copy of the Cleary version of the Blue Cliff Record in case he wanted to quote it if called upon to address Zen students: “According to the Buddha Name Scripture, a sun-faced Buddha lives in the world 1800 years, whereas a moon-faced Buddha enters extinction after a day and a night. Tenkei Denson said, ‘But is everyone’s own Sun-Faced Buddha-Moon-Faced-Buddha something long or short?’”

He said from now on he would be more responsive to young book fans who write and ask deep questions. “I always backed away before because I never knew how to deal with that, but now I won’t. Each one of them is a Chris.”

Bob spoke again about what “Chris” now was, static and dynamic, living and dead, and just what it was Bob lost and gained and what caused the pain. One thing we had gained was a huge presence of Chris’s absence.

That morning Bob called his old friend Abigail Kenyon to invite her to the funeral. It turned out Nancy or Ted already had. Abigail related details she had learned about the vigil at the mortuary that had occupied many Zen students throughout the five days since Chris’s death. Two students at a time, on two-hour shifts, sat zazen meditation with his body 24 hours a day. Later I asked Meg who they were, and she named her husband, Marc Alexander, and a priest named Linda Cutts. Meg said there were many, many others, but she refused to give names, saying we would have to ask Robert Lytle, Reb’s assistant.

Abigail had learned about the vigil from Ted. She said he had fallen asleep during his shift and, on waking, felt peaceful and happy. After the call with Abigail, Bob said what happened to Ted at the mortuary sounded like an enlightenment experience.

That morning the sun was shining and the temperature was about 50. The weather in San Francisco wasn’t as cold as England in late November, and the daylight was longer, as it got light around 7:00 am and dark around 5:00 pm. So before breakfast, we decided to take a walk down Market Street. We told Meg we’d be out walking if anyone wanted us; we were under the impression that people would.

Most of the buildings near City Center are two- and three-story, tall-windowed Victorians, fairly well painted. From the Laguna-Page corner, as well as from other vantage points including our upstairs windows in the Guest House, you could get nice views of lower parts of the city and white skyscrapers. There were some trees. But the overall effect was not one of beauty; it just took a few ghetto faces to remind us of the murder.

We followed Page down the hill and under the freeway, then onto Market Street’s brick sidewalk. The street was full of trackless trolleys, buses, and cars. Looking toward the southwest end of Market Street you saw twin peaks of green “mountains” even from here in the city. I thought of how many times Chris would have walked this same way, probably even just days ago. Market was full of stores and pedestrians, lots of fast-food places and 24-hour joints, and hi-fi stores with bars on the windows, etc. Blacks and Whites, and ratty, mean sorts of characters, lots of doped out young men. Bob bristled each time we saw potentially violent-looking guys.

I continued to feel sort of protective toward Bob, watching his expression and worrying about him absent-mindedly stepping in front of cars. He was deep in thought, while also absorbing the sunny-shady streets. The winter sun was low in the south, so no street was completely sunny. We walked for hours, to the Embarcadero, where he recalled sailing for Korea in the Army in 1946. We skirted Chinatown, then trudged uphill toward Telegraph Hill, where he recalled trips with Nancy in the 1950s. In their days employed at a Nevada casino when first married they used to bomb down for a weekend, and always began with a martini at the Top of the Mark. I was amazed how steep some streets really were; on some, cars had to park sideways, into the curb.

It was noon when we got to Fisherman’s Wharf and we still hadn’t had breakfast. The area was getting crowded with tourists, jewelry hawkers, and stands selling crab legs and fish. We were famished and headed into a restaurant and ordered expensive fried fish platters. Our manic mood continued. We smiled at each other a lot and felt very tender.

“Is it possible,” Bob asked, “that at this moment, in this same beautiful city, my boy’s mutilated body is being turned back into gases and dust?”

We felt a fresh consciousness of the reincarnation mystery and the idea of a transference of Chris to me. Often Bob would look at me with wet eyes and grin, saying, “Hi, Chris!”

The waitress was a hassle for us, and vice versa, because we were thirsty and wanted six or seven refills of water, while she preferred talking to some customer at the bar. There was still very little lunch business. She kept growling, and I kept apologizing and smiling at her. She was so nasty that we finally got laughing about her and Bob had me tip her extra. As we were leaving, she seemed to be starting to be nice to everyone in the place, and we laughed some more. Bob had thrown away her bad karma, and he related this to Chris; this was also a kind of reincarnation.

From the wharf we climbed a steep street and looked back at the blue bay. All kinds of vegetation flowered here and there, and we came to a park which was mostly trees with a walkway and steps coming through. We sat down to peer out at the water. A spot of sunlight was hitting a trio of purple flowers forming cone-shaped figures, and as I watched them, once again I experienced the presence of Chris.

This time I imagined he was concerned about Nancy. I had been worrying about her arrival and the effect of my presence on her. I worried she would resent me, and at the same time I resented her sharing Bob’s past, the years I could never share, those heady days they roared through the Sierras and Downieville and clinked glasses at the Top of the Mark. These were the days Bob said were the happiest of his life. What the Chris-ghost had to say was: get compassion. Feelings of competition, feelings of jealousy: let them go. The way to be kindest to Nancy during the coming weekend is to be empty.

We walked back across Nob Hill and through wealthy Chinese neighborhoods. Toward Market Street we began to comment on the differences between good faces and bad. We were more and more tense the closer we got to Page Street, glancing behind, holding tight to our traveling bag.

Near Zen Center we stopped to look at the big pale blue mural we’d seen the night before. It covered the whole length of the outside wall of the Guest House. It made the little park seem bigger. It seemed Hindu and therefore not a Zen Center thing. A Krishna-type character played a gigantic flute in a garden with friends and exotic animals.

We sat on a bench to look at it, and then along came Reb, with two other people he apparently was showing around. He left them and approached us, looking at us with his big, moonbeam gaze and smiling. He said something about having had a good time the night before, and we agreed.

Then we talked about some old Chinese Buddhist prayer beads Chris had. Bob had originally gotten them in Shanghai, back when he was a soldier. They were beautiful large red-brown beads carved into heads. Long ago he had given them to his friend Abigail, asking her, “Which one is enlightened?” —one bead had a third eye on his forehead. When Chris had gone to California, Bob had mentioned Abigail as someone he could ask for help. When they met, though, Chris asked her for the beads. Hearing this, Bob had scolded him. Writing Abigail, Bob called Chris a Zen rascal, telling her, “He loves wearing pretty ju-ju beads, but what is he doing for mankind?” In that letter Bob had challenged her to get Chris to earn those beads by teaching her about Zen. Reb smiled as Bob related all this. He knew the beads. “They’re the ones with the heads,” he said. Bob told him that this was “unfinished dharma” and that Abigail would be at the funeral. As for the beads, he said to Reb, “I would like those to be yours.” A flash of pain or regret crossed Reb’s eyes for an instant, but he accepted, saying something simple like, “Okay, thank you.”

Reb’s companions were still waiting, but I asked one more thing. Packing our clothes in England I’d forgotten a necktie for Bob to wear at the funeral. Could he borrow one? Reb smiled and said sure. Later I asked Bob if that had been wise, and he said, “It was perfect. It’s the way Chris would have done.”

Bob said to Reb, “We understand Baker-roshi is arriving today from Tassajara?” but Reb was vague, like he didn’t know and it wouldn’t affect us anyway. The rest of the day and evening we stayed in our room. We expected people from Zen Center would come to see us, but nobody came.

We still wished we knew more about what had happened, and what was going to happen. Sounds of the street drifted up: buses, cars, police sirens, Black male voices. We reflected on all our impressions since arriving in San Francisco. Bob fantasized about being claimed at Zen Center as a “father figure,” but so far there was no evidence of anything like that. We talked, ate fruit from Meg’s basket for dinner, and went to bed early. There were no restaurants or even supermarkets nearby without crossing dangerous territory.

We saw Meg again. As before she seemed hesitant about us, not hostile but concerned about something. Now it was explained. She took me aside and asked advice on “the family situation.” Should Nancy and Ted stay in the Guest House, or would relations between her and me make that distressing? And Katagiri? I checked with Bob, and then told Meg that it was all right with us if everyone were at the Guest House. Meg referred to setting up chairs for the funeral service, and I explained that we all practiced zazen and regular cushions would be no problem. Always she looked at my face thoughtfully with complete reserve, showing neither approval nor disapproval.

In the night a Chris ghost appeared to Bob for the first time. He told me about it the next day. It appeared 15 feet tall out of a vague shadow across the room. Bob thought about how vague it looked, and then Chris seemed to say, “I can make myself clearer, Dad,” and did. His face was peaceful, empty. Bob asked, “Chris, did I fail you?” The ghost didn’t answer; emptiness was the answer, and the image disappeared.

| 2 |