(Note: click on tiny images to display additional photos.)

Saturday, December 22

Katagiri arrived at our quarters in Peter Coyote’s apartment. I had planned to drop in at his room instead just to give him the calligraphy, but Steve called saying that “Roshi’s schedule has gotten complicated” and he would like to see us at our current abode. We wondered what this meant. Katagiri arrived with some Christmas cookies someone had given him. It was an awkward meeting because he had an idea there was more to it than the calligraphy gift.

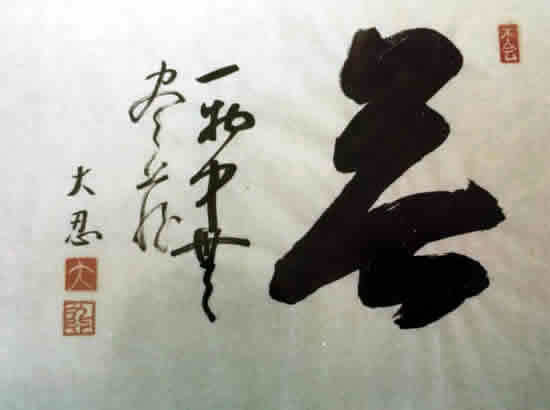

"Within nothingness there is a inexhaustible working."

First Bob showed him all Peter’s weird stuff and talked about American Indians. Then they went into the living room and Bob explained peyote’s religious function, how it was legal for Indians.

Then he said Reb had told us Katagiri wanted the calligraphy, but Katagiri said no, it was a photo that he had wanted. This produced more confusion because Bob assumed he wanted a picture Maynard had taken when Chris was a little boy, rather than the recent photo that Zen Center had displayed at the funeral.

When Bob told Katagiri this was all we’d wanted to talk to him about, we figured he would be on his way, but instead he accepted a second cup of tea and a book Bob had been sent galleys of called Into the Quiet. That led Bob to talk more about alternatives to ritual in American Zen practice, and the history of animosity between Catholics and Protestants. He said, “the reason more Catholics than Protestants are receptive to Zen is because they are used to religious ritual.” Bob said these were fundamental value differences, and often it became clear in a few minutes’ conversation whether someone was raised a Catholic or a Protestant. This seemed to interest Katagiri. We discussed Baker, and all three of us were speculating that though he was not Catholic he could be Episcopalian because he was so fond of ceremony.

Katagiri said, “Yes, he likes ceremony. I tried to tell him, at the Suzuki ceremony last time, ‘That’s enough.’ But he doesn’t listen.” He laughed, and of course Bob was delighted.

Then the phone rang and it was Steve Allen, urging Katagiri to get to his next appointment. Later Bob said he was embarrassed at taking up so much of his time just to offer him the calligraphy. He was with us for an hour.

We spent all midday in bed together. Bob was gloomy again but a little less than the day before. We got out an atlas and thought about the upcoming trip to Minnesota but he wasn’t enthusiastic. We’ll do this or that, go here or there, “the three of us,” meaning Chris would be along.

Once again he reviewed the good things about Chris’s death—that he was spared more years of struggle, that he had had some happy years, that he didn’t die when he was just 10. This was followed by more despairing, revengeful thoughts about the lawless culture. He fantasized about a kamikaze attack and then, seeing me worry, said, “Not now.” Years from now, when he would be 65 or 70 and had terminal cancer or something, “Why not take a few of these guys with me?” He noted that the Cheyenne often did this; a warrior would say good-bye to his friends, give away his possessions, paint his body white, and then ride away into the enemy camp never to return. Everybody was afraid of the Cheyenne; how could you defeat someone who was not afraid to die?

But then his thoughts returned to the book. Lila would now be much more powerful. “This is where I should be devoting my energies, not to a handful of Zen Center people in California, but to readers all over America.”

He didn’t seem angry at Baker. He said good things about the restaurant and Baker’s financial abilities.

Fudo came back! He’d been gone two and a half days. After he reappeared I half expected to see Chris. I’m not going to let him out anymore.

Sunday, December 23, Ashes Ceremony for Chris

I had stayed up late reading Ringolerio. So I was slow to wake up Sunday morning, even when I felt Bob crying and hugging me.

“What are you thinking about?” I said.

“Chris,” he said. “It is a stormy day and it’s going to be perfect weather for the ashes ceremony.” As I listened I could hear wet tires on the pavement, and the wind was gusting and rattling the windowpanes.

We didn’t have a ride to Green Gulch, but I’d learned the day before that a Zen Center bus left at 9:00, so a little ahead of time we left. Bob wore his navy trench coat over his usual baggy gray sweater and navy pants, and he carried Chris’s black umbrella. I wore my only raincoat, a yellow rain slicker from the boat, over Chris’s black mohair sweater, a long brown skirt, and white sneakers. Also Chris’s electronic watch and the brown Buddhist beads he had once given me.

Almost a dozen of us eventually crowded into this van, and a cup was passed around for 50-cent fares. A good-faced student named Jim, the driver, asked us all to fasten our seat belts. The rain was slow and steady, and the windows steamed up.

Behind us in the vehicle was a load of bread from the bakery, plus Barbara Horn, who was tired from working at the restaurant and fell asleep on the lap of Linda Hess. Despite having someone on her lap, Linda found the trip a golden opportunity to “discuss” with Bob, and again posed the question: “What does it mean to be unattached to your writing?” We were all more relaxed than we had been the last time we talked with her. She had been writing scholarly articles, was now finishing a book on a Sanskrit poet, and wanted to also write on a more personal theme “which I am not prepared to discuss.” She told us she was getting her Ph.D. from Berkeley. “That’s a good school,” said Bob.

“I sit zazen, go to sesshins,” she said, “but I never make time to go to Tassajara.” What did Bob think about that?

Bob took the same attitude he did with me: trying to get her to un-attach from her intense concern about attachment. “To go to Tassajara in order to get yourself to not attach to writing might be wrong,” he said, “because then you’d be attaching to Tassajara.”

Linda was dissatisfied with everything Bob said. As soon as he made a reply she tried a new idea, such as, “Baker-roshi said in dokusan one time that while D. T. Suzuki had made a great contribution to the west’s understanding of Buddhism, his own understanding wasn’t complete.” She asked Bob to please not repeat that treason, but—what did he think? He neither agreed nor disagreed, but I giggled that he had once said the same thing about D. T. Suzuki, and he joked, “Shhh!”

She then questioned Zen Center’s wisdom of assigning people rotating jobs rather than allowing specialization, like hers. Bob neither approved nor condemned it. (Later he said he had been tempted to remark, “Yeah, everybody rotates all the Zen Center jobs except one!”)

Linda kept this lively discussion going all the way to Green Gulch, with everyone in the van tuned in. The wide multi-lane highway carried us across the Golden Gate Bridge, through the rocky, treeless park. Across the bridge, through the tunnel.

A stranger up front asked whether Bob’s new book would be on Zen and the art of sailing, and Hal, who didn’t know who Bob was, asked what he had already written. It was the kind of exchange Bob loved, and afterward he said he liked Linda a lot.

At Green Gulch it felt good to be in the barn again. Even though we had only been there when Katagiri lectured the morning before the funeral, it felt familiar and comfortable with the unfinished wood and sounds of rain. We pushed the sliding doors back and took off our shoes and raincoats, then passed through the high-ceilinged room where students have their quarters around a balcony upstairs, then went into the zendo, which also doubled as Buddha hall. That’s why we liked it: less folderol than at City Center. One room served for everything. One big rough-looking Buddha with a candle and a kerosene lamp. Fewer people wore robes, just the priests. Other people could wear rakusus over their ordinary clothes. Half the people didn’t even have that, they were just regular people sitting in chairs.

We sat on cushions near where we had sat four weeks before with Nancy and Ted. Dan Welch and Blanche Hartman took seats near us. Even though we hadn’t spoken I liked her now, bald though she was. There was just something good about the way she came in and sat down next to Bob.

We hadn’t known who would lecture, but it turned out to be Baker himself, at last. He had a pious tone in his voice. While lecturing he rested his hands on his roshi stick, which was ornately carved with a curled S at the top. His theme was that the way to approach the unanswerable questions in the world was to meet them with an acceptance of the unanswerable in ourselves. He spoke for an hour and laced through topics from ESP, and the fact that monkeys on three islands off Japan began washing sweet potatoes on the same day ✽with implications for a nuclear freeze—discredited wishful thinking - DC; to world violence and the Ayatollah Khomeini, and how we were now closer to World War III than ever before. Things were not finite and objective. Many things were the moon. A pond’s reflection was the moon. Your menstrual period was the moon. He occasionally laughed in a way that seemed forced. Two or three times I worried that Bob would “harrumph” out loud in disgust. Baker kept repeating one koan: “If the golden dragon leaves the water for just one moment, the garuda bird gets it.” It seemed to have nothing to do with anything, yet he repeated it several times, and in front of us a lady laughed each time as though it were a great joke. The talk resembled a Christian minister’s sermon, except that instead of asking us to accept Jesus he asked us to accept “the unanswerable in ourselves.”

On the way out of the zendo I saw an old man in slippers sitting on a chair, and apparently he was waiting for everyone to go by before he left. Beside him was a girl my age with a tragic, angry look on her face, and I realized then that the man must be the dying Alan Chadwick. His hair was white and he looked thin and tired, and he did not look at anyone as we filed by. His striking, contoured face was serene and alert and kind, though, and I felt glad he had found a good place to die.

As we went out to put our shoes on in the hall, where everyone was chatting and talking, we looked up to see that from one of the upstairs rooms along the balcony, Reb had picked up his three-year-old daughter Thea and was starting down the stairs. He saw us and smiled. He was dressed in his black robe and rakusu, and it occurred to me that in all the time we were at Zen Center, we had never seen him in other than formal Japanese priest robes. Today he seemed to walk with trouble because not only was he carrying his little girl downstairs, he also wore some strange wooden Japanese sandals set on one-inch legs ✽geta, wooden platform sandals - DC.

I was glad to see him. Except for zazen at City Center, Bob hadn’t seen him since we had decided to leave San Francisco, and their last conversation may have been at the Eheiji Abbot dinner. I called out to him cheerfully and said, referring to Thea having been upstairs, “Hey, here comes the peanut gallery!”

“What?” he said, not quite hearing over all the conversations, or perhaps being too young himself to understand the reference to the old Howdy Doody television show. “What about peanuts?”

Then suddenly one wooden sandal gave way and to our horror Reb began to fall, stumbled, and at last crashed to the bottom of the stairs, using his arms to just barely keep from crushing Thea. There was a gasp from everybody, and people rushed forward. Fortunately he wasn’t hurt and Thea just looked a little frightened and whimpered a bit. He picked himself up and, with that tense look I’d seen before, he greeted us.

“What about peanuts?” he asked with a smile.

“Nothing!” I just laughed and tried to be calm. For a few minutes we stood quietly while crowds of people checked Reb over.

“You okay?” someone asked.

“Sure, except for my two broken legs.” He seemed so crushed and embarrassed and disturbed that I felt like hugging him. He went on to ask what our plans now were.

I explained that we were staying until New Year’s for reasons relating to Peter’s animals and my teeth. Bob said we were going to put Chris’s things in a truck and head to Minnesota, where “my 78-year-old father is all alone in a big house.”

Reb said of the ashes ceremony later today, “Roshi says the ceremony will be quite small, because of the rain.” We asked how far up the hill it would take place, and he said it would be about half a mile, above the outer parking lot.

“Near Alan Watts’ marker?” Bob asked.

“Kind of.”

“Is there any significance in the location,” I asked, “or is it just a nice place?”

“It’s just a nice place.”

Reb moved along and we got some tea, and then along came Yvonne Rand, warm and upbeat

“I’ve just started reading your book,” she said to Bob. “You know, I have never read it before.” Yvonne’s last word was that we must do lunch some time.

We could have attended Sunday lunch at Green Gulch but instead Bob and I got on our shoes and rain stuff, and then under rainy skies went on a diversionary hike down to the ocean for the next three hours.

At the bottom of the gulch we reached a road that went past some houses, through a tall eucalyptus grove, then on toward the beach, where we began to feed upon the wind and the roaring noise and the cold blasts of air that numbed our ears. The rain made the eucalyptus smell very strong, and the wind made a sweeping sound in the leaves and branches. It was hardly raining and we couldn’t use our umbrellas in the wind anyway, which seemed like a good 30 knots from the south and made our eyes wet when we reached the beach. The sand was cut in two by a surge of ocean water that flowed diagonally inland from the surf, and beyond the second part of the dunes, the surf was huge. There was a strange illusion that the ocean was actually a slope that rose up from the beach to the western horizon; perhaps it was our perspective looking along the beach, or the relationship of the beach to the steep cliffs that spread up and down the coast from this valley, or perhaps it was the size of the seas themselves. After a while we turned out of the wind for relief, and looked back at the gray-green hills, and off to the cliffs on either side. To the north a couple lonely palm trees waved wildly, and to the south the misted black cliffs looked formidable. It would have been a deadly coast today for a sailboat.

We went on to the Pelican Inn, where we had had ginger beers with Peter. Bob ordered a “ploughman’s lunch” and then was disappointed when it turned out to be just rolls and a couple pieces of cheddar. I shared my “shepherd’s pie” that was much better. We had been eating mostly vegetarian and Bob was craving meat.

We headed back up the two-lane highway. Horses grazed on the steep hillsides, and two gray deer scampered up the wet hill from the road. Cars with California plates whizzed by every few minutes. One was a hippie-mobile, a VW bus painted pink, with a roof made from the body of a VW bug. Below us roared the gray Pacific.

I was caught by thoughts of Chris, especially of his life here at Green Gulch when he first arrived in this magic valley. As we climbed, a hawk suspended at our elevation on the road hovered over the center of Zen Center’s farm hundreds of feet below. From the road we too had a bird’s eye view of the random-looking truck gardens lying like green handkerchiefs below, with neat compost heaps, chicken coops and special piles of eggshells. They were the only flat surface; beyond them, across the valley, hilltops seemed close enough to touch even though it would take hours of walking to reach them. They were gray-green. This could have been named Gray-Green Gulch.

Finally a mile or so from the Zen Center buildings we crossed another stretch of eucalyptus lining the dirt hairpin drive in. I picked up some eucalyptus berries and noticed how they were covered with light blue powder that wiped off.

“Dynamic quality,” I said, making Bob laugh.

Back at the farm we started for the meeting place for the service. The ground all over Green Gulch was mud because of the rain, and we slogged to Baker’s house, where the entryway was crowded with huge bushes. The yard was entered through a beautiful bamboo gate six feet tall, and some kind of wind bell was getting a real workout in the storm.

We went in and found things very busy in the kitchen, all sorts of people milling around. John Bailes showed us into the living room and brought us tea and cookies. Ginny came in friendlier than ever and sat beside Bob on the couch, Yvonne came in, and Renée des Tombe came with Elizabeth, who had just gotten up from a nap. We enjoyed a baby performance, watching her toddle around the living room and attempt to climb onto the beautiful redwood coffee table ✽I built that table - DC, crunch the flowers, eat all the cookies.

Gradually we became aware that in an adjacent “tatami room,” ceremony preparations were underway. Katagiri appeared and went into the special room, with Steve Allen, Reb and others following. Out of our view there was much scurrying about. Reb returned and asked me for a calendar, but all I had was one for 1980. (It turned out the service would make a reference to the exact number of days since Chris’s death.) A tall, reddish carved wood plank, perhaps cedar, was brought in and later removed, evidently after Katagiri painted on it. Baker came to the living room and shook hands with us, then told a story of Elizabeth being cute learning toilet behavior, how she had made grunt sounds while pretending to sit on the toilet and, which he demonstrated to everyone’s embarrassment. He handed me an obsidian relic to admire, an old Native American knife found at Green Gulch. Then came word that “two members of the family” were waiting at the Wheelwright Center, and to our surprise, Bob’s in-laws, Judy and Geraldine Jobes, were brought in. I had an extra set of photos from the funeral and gave it to them, and told them their letters had been posted on the City Center bulletin board.

At last everything was ready. The rain was back again. Ginny told us the worst storm of the year was being forecast. She said it apologetically, but Bob’s eyes twinkled when he heard it. Ginny recalled the ashes ceremony for Suzuki-Roshi, and said it started with a peaceful night and yet blew into such a gale that all the chants were thrown off, people held onto one another, and the ashes scattered instantly all over the hillside.

After a while we heard the densho bell, and the priests and Baker and Katagiri emerged from the tatami room, and then there was a general confusion of boots and shoes and umbrellas in the tiny entryway of the house. Reb came over to Bob and said in a quiet voice, “We’d like you to carry the ashes,” just as he had spoken to Nancy at the funeral, and a look of pain crossed Bob’s face just as it had hers. Reb put the white sling around Bob’s neck with the knot in back, and he was given Baker’s big black umbrella to carry in one hand while he steadied the bundle in the other. Reb then asked me to carry Chris’s picture and to go and get it from an office upstairs. I brought it down and set it on the kitchen table, and then had to figure out how to get my sneakers on in the entryway but not walk on the kitchen floor; I finally asked Geraldine to help me. At last I was outside in the rain opening Chris’s umbrella, and the procession began. We heard that sweet, sad, two-tone bell again through the sound of rain on all the umbrellas. I couldn’t tell if it was behind us or ahead.

The feeling was much different than the funeral. Chris was much more present here. We went single file on the gravel-and-mud-and-pothole driveway through the eucalyptus stand, the rain now pattering steadily. The top of my vision was framed by Chris’s black umbrella, and just underneath it was the white knot clutching the back of Bob’s neck like a child’s hands. Bob later said he spent this whole part of the trip thinking of all the times he had carried Chris and was glad that he could now carry him.

So all the way I just watched Bob’s shoulders and back and legs, and the drips in the puddles, and my muddy sneakers, and the gray-green eucalyptus leaves and shreds of reddish bark. At the center of the procession my embarrassingly bright yellow raincoat contrasted with the dark black robes of monks plodding ahead and behind. Lying across my bright yellow arms, cradled in one hand while the other held the umbrella, was Chris’s face, which I watched upside down and thought of how much pain Bob felt right then, and how much pain Chris would have felt to see those sad shoulders and the bent head. And so for quite a bit I cried again and it was another one of the 4,000 times in the last month that I felt I was marrying again.

The procession came out of the trees and through the parking lot and climbed up a grassy path for a while, and the rain and clouds dimmed the view of the steep hills up ahead as the ravine narrowed. Pretty soon I saw a clump of people ahead and realized more Zen Center people had gathered for the service and that we had been just walking in the procession of priests. A lot of the others had bright yellow raincoats too, and actually the effect of the random yellow splashes was rather nice among all the black of the priests’ robes and all the earth tones of the valley and the gray of the sky. Also, Baker and several others carried large Chinese umbrellas that were bright orange. Katagiri’s and Baker’s robes were different from the black robes of the other priests; they were dusky brown and gray or blue. I forget who wore what.

Many of the American priests, including Baker, wore those crazy Japanese wood sandals like Reb fell in, and Reb still wore his. I was amused to notice that Katagiri wore stout black rubber boots. No fool!

The waiting people were all lined up facing down the trail towards us, and as we reached them we all moved past with many entanglements of umbrellas. I was shown to one side of the group and Bob and Katagiri to the other, and the ashes were taken. Bob looked older than I had ever seen him, and very tired, and for the next ten minutes I seldom took my eyes from his face, though I often lost sight of him through the umbrellas. I actually wanted him to look at me at that point, in my yellow raincoat holding Chris’s picture, and finally after a while he did, and brightened up a little, though not much.

A jisha held Baker’s umbrella, and Steve also watched over Katagiri like a guardian angel. The area where we had gathered was covered with scattered straw, and at the head of it was a beautiful stone about two feet in diameter, sort of round and flat like a pushed in zafu or zazen cushion set on its side. I knew Bob would like it. On the ground in front of it were some pretty pink seashells and a feather. Before the stone stood a card table covered with a cloth, a candle, incense, water bowls and all sorts of other hocus pocus. One of the priests had to stand over it with an umbrella. Baker turned toward me for the picture and set it there too.

Baker intoned some stuff in Japanese and English, the gist of which was that we were here to pass out of mourning and clinging to death so that all that would remain was a clear, bright memory of Chris. Reb unwrapped the tall wood marker that Katagiri had painted, and secured it in a hole behind the rock. I noticed that Bob didn’t have an umbrella anymore and was getting all wet, and then Steve Allen came and “jishaed” Bob with his umbrella, as somebody else was sheltering Katagiri at that point. Finally Bob wound up next to the stone, with Reb under his jisha’s umbrella, and Baker and his jisha on the other side, Katagiri and Steve just down the slope from Bob and Reb, and I stood opposite them. I felt throughout the whole ceremony that the priests around me were being very protective. Katagiri was wearing his fierce, stony frown, like an immovable stone roshi. His eyes stayed on the rock, or sometimes on the trees or the ground. Reb too had high importance in the ceremony, and his face had that same look of emotion we had seen earlier, pain and stress. I was glad he and Bob stood close together.

At one point through the umbrellas I could see that the container Bob had carried was now unwrapped, and what looked like a small pile of crushed bones sat in a dish on top of a jar. Katagiri then went forward and did something I couldn’t see. Then Baker handed Bob some chopsticks. The idea, it turned out, was to take a piece in the chopsticks, pass it over the incense burner (“if you want,” said Baker), and place it in a hole dug under the rock. I didn’t know how Bob would manage this with his shaking hands, or me either, once Baker turned and asked me to do it too. But Bob took his turn. Then he turned and handed the chopsticks to Reb, which was not in the script. Reb gave him a startled look and handed the sticks to Baker.

I took my turn and the piece didn’t land in the deep part of the hole, so Baker moved it. I think at this point Geraldine and Judy were invited to follow, and Reb also took part. At one point I saw Bob and Reb exchange warm glances. The rest of the ashes were all poured into a paper funnel which fed them neatly into the hole.

And then it began to rain harder than ever. Baker continued intoning, but we could hardly hear what he said for all the racket on our umbrellas. There was something to do with water; we were all invited to ladle three ladles full of water over the rock. This took a while, and during the process some gusts of wind started to catch a few umbrellas and knock them into each other. I looked at the hills, and whole sheets of rain were being blown up the valley, and there were howling and whooshing sounds. Baker continued his ceremony in English and Japanese. I think there were some bananas and apples being offered in some context, but these niceties were starting to get really lost in the wind and rain and bobbing umbrellas.

Then, all of a sudden, a huge blast of air roared up the valley and tried to bend all the umbrellas inside out. Bob and I looked at each other. He was beginning to look gleeful, and I started to feel euphoric. We all began chanting a short Japanese chant that I had now learned from the morning services. It was repeated over and over, and as we chanted the weather chanted too, completely drowning out our voices. Chris’s umbrella got caught on the poncho of Robert Lytle and one prong sprang, so Robert spent the chant trying to fix it while I watched, and it all felt very friendly. The chant ended in an absolute fury of wind and rain.

Baker’s ceremony was over. Reading from notes, he said that we had offered “something from the air and sea, we have offered food and water,” etc. and he recited how many days since Chris had died, and said, “This is your new home.” He asked Bob and then me if we had something to say, and we said no. And then, as the valley roared and the sky grew dark with approaching night, everyone started milling around and going down the hill. Someone offered me their umbrella, since Chris’s was now broken, but I was fine and just pulled up my yellow hood. Then I went to Bob, who now looked radiant and strong again. He was so pleased with the weather.

“Priests zero, shamans one,” he said later.

So we then all tumbled and slid down the hill. Baker and Katagiri disappeared. Students helped carry down all the gear like the card table. Dan Welch bounded along with some folding chairs, and Bob shouted to him about how this day was meant for Chris, and Dan smiled. Dan recalled the big storm that happened at the Suzuki-Roshi ashes ceremony. Dan didn’t shout, though. Everyone was quiet except Bob and the storm.

Right ahead was Reb, sliding along in his Japanese sandals trying also to hold both an umbrella and a brass incense burner while keeping his balance. He looked back and when he saw me I smiled, but he didn’t. Instead he said, “Would you carry this please?” and handed me the incense burner. Bob was now carrying Chris’s photograph. It was getting soaked. I asked him about whether we ought to give it to Katagiri now, and as we reached flat ground he stepped up to Reb to ask him, and for a while they walked side by side. Then Bob stepped ahead and Reb dropped back. I was behind both of them, and at one point Reb’s robe snagged a big branch that had fallen in the road, and I unhooked it. Eucalyptus branches, bark and leaves were everywhere. When we got to the dining room I held the incense burner until Reb came and took it.

In the dining room, the 20 or 30 of us who gathered shared that hubbub of excitement that stormy weather sometimes brings. Bob was grinning at everybody. Issan Tommy Dorsey came and said some things and then put his hand on Bob’s shoulders, which brought tears to his eyes. Tommy’s face was all red, and he too recalled the storm during the Suzuki-Roshi ashes ceremony.

Katagiri came in, unaware of Bob’s mood and looking doubtful. Bob looked at him and called over, “Good storm!” and Katagiri’s face burst into a smile.

Soon Baker arrived and sort of called the meeting to order, saying that we would reassemble in the Wheelwright Center living room for tea, and to finish the incense offering that was interrupted. Apparently at the end they had been trying to light incense and it wouldn’t go.

Then he said, “I think Chris would have liked this weather,” and looked at Bob.

“He would have loved it,” Bob roared, punching a fist through the air and grinning. Everybody laughed. “He was born in a storm, and his whole life was stormy too. He would have called this perfect weather.”

We reassembled upstairs. I saw Katagiri greeting people by saying, “Good storm! Good storm!”

Upstairs we all sat around a big wood stove while puddles collected under our chairs, and Baker came over. We talked a bit about our crossing the Atlantic on our sailboat, and he asked us questions but I felt he wasn’t listening, just trying to fill up time as the other people arrived from outside. He said he had experienced hurricanes in the Merchant Marine. He told a story about a sailor on deck who showed another guy a watch and asked, “Isn’t it beautiful? You can have it for $50.” The guy looked at it and threw it overboard. The first sailor said, “Okay, I’ll take two dollars.” Baker laughed, but we wondered what his point was.

Then, at a little altar in the corner of the room, the Prajna Paramita Sutra was chanted in English and Japanese, and then the sutra I knew simply as the “Boryo Ki” was chanted twice, while everyone walked in a line. And then, Baker turned to us and said, “We want you to know you are always welcome here. We may have lost Chris, but we gained the friendship of both of you.” We gasshoed and said thank you, and felt surprised.

There was a big square coffee table with chairs all around, and a couch at one end where Baker sat down to eat pfeffernuss and poppyseed cake, etc. I was sitting on the rug next to Bob. After a few minutes Baker said, “Hey, doesn’t anyone want to come over and keep me company?” His words were mostly lost in the general conversation noise and nobody picked up, so I went over and sat next to Baker. He didn’t acknowledge me at first. Then I passed a plate of cake to somebody else, and he said, “Hey, what happened to the cake?” and slapped me on the leg.

We chatted about a crazy Christmas tree beside us. Almost as wide as it was tall, it seemed to be a pruning from an overgrown evergreen, decorated with lights and edibles. Baker noted that it had three tops, so instead of one star it could be topped with the Buddha, the Dharma and the Sangha. When he spoke he addressed the entire room, although few people besides me were listening.

“You look a lot like Chris,” he said. I laughingly told how some people at Zen Center had referred to Bob as my father; Baker seemed a little surprised and uncomfortable about this anecdote. He replied by saying something like, “You don’t really look that young.” But I said my relationship to Chris felt sisterly.

We talked about Maine, where we had been married and he was born. His ancestors were among the original settlers of Maine, he said. We discussed Cromwellians vs. Royalists, and how both his ancestors and some of mine had arrived soon after the Mayflower. He told me with great seriousness that his middle name was Dudley because he was descended from the Dudley who was the second governor of Massachusetts. I told him I was descended from English wheelwrights; he reminded me he was a Baker.

Meanwhile, across the room, Bob was having a conversation with Ed Sattizahn, Blanche Hartman, and others. It related to part of the koan Baker told in his lecture, “If the golden dragon leaves the water for just one moment, the garuda bird gets it.” Ed thanked Bob for the check, and Bob remarked the expenses were slight compared to what Christians charge, and said the gravesite was beautiful. Ed hinted that Zen Center could use more funds and that donations were gratefully received. “Oh-oh,” Bob later said he thought to himself. “Looks like I am the golden dragon, and this is the garuda bird.”

At one point Yvonne came by and began saying something about where they were going for dinner. Baker spontaneously invited us to join them “if there is enough food,” and Yvonne went to check. I said I wondered how we would get back to the city afterward, and Baker offered to drive us. “I don’t have anything else to do.” Yvonne gave him a wry look.

We moved into the Bakers’ kitchen to get ready to leave with them and Katagiri; we still didn’t know where. Bob gave Katagiri the picture of Chris.

A woman named Antoinette, the sister of Tony Artino whom we had known in Minnesota, was bounding around the kitchen doing some chores and being friendly. Bob and Katagiri got into a funny discussion about getting old. It was very chummy, the two of them relating like two old men in a bar, tapping their fingers together, rocking back and forth and laughing.

“You and I are same age, right?” Katagiri said. Katagiri’s older son was 18. He said he would look as old as Bob if he didn’t shave off everything turning gray. Bob said he liked looking old, it commanded respect. But then he began talking nostalgically about our possibly going to live with his father if he needed us. He became a little emotional, and Katagiri just listened quietly, turning into a roshi again.

The three of us followed Baker into his car. We had no idea where we were going, but Baker started to ask if we had ever heard of the “famous” film director John Nathan. He seemed a little disappointed to learn we had already met him. We told him about Farm Song, and Bob’s hopes for Nathan and a ZMM film. Katagiri knew Nathan’s wife, Mayumi.

We arrived at the Nathans’ home in the middle of a power outage; it had been one of the worst storms in the history of the Bay area. It had blown 60 mph and taken down power lines. Fortunately Mayumi had already cooked dinner, but we would be crowding in wet clothes around a low 4x4 foot Japanese “electric table” ✽kotatsu - DC that had gone dead. For light there were candles and flashlights. Everybody but us drank sake and wine. In addition to Katagiri and ourselves, the party consisted of Ginny, Sally (a pretty, quiet, dark-haired 17-year-old) and Richard Baker; John and Mayumi Nathan and their two small boys ✽Zack and Jiro - DC; Yvonne and Hillary Rand, and Renée des Tombe.

Mayumi said the dishes were Korean; the food was tangy and invisible in the dark. There was lots of physical contact between everyone and especially the little boys. Bob and Baker sat across from each other and never addressed each other. John Nathan related warmly to us this time and told lots of jokes. He spoke in Japanese to Katagiri, with a fluency that amazed him. Mayumi took Katagiri around the house with a candle to look at her artwork. John had gotten an offer from PBS, and he and Bob talked about making a film on the Midwest or Minnesota. Ginny joined enthusiastically, and said to Bob, “Right from the start I felt comfortable with you, because there is something Midwestern there.”

Yvonne talked about Peter Coyote. She told us to get him to show us photos of himself going around with Hell’s Angels and riding Harleys with long hair. “He looked ten years older than he does now. And mean!”

Toward the end of the meal, as we were all still sitting around by candlelight, someone arrived at the door, and Yvonne looked up with an expression of rapture, and yelled, “Christopher!” Bob and I gasped in surprise before remembering Yvonne had a grown son named Christopher. Everybody’s hilarity as he came in contrasted with our thoughts of the wind-driven rain soaking bones and ashes up on the hill.

After dinner Baker relaxed by sprawling on the floor. It was determined that he wouldn’t drive us into the city after all; John Bailes would. So this would be good-bye between Baker and Katagiri, both of whom were a little drunk. We were by the door, I was trying to get my shoes on, and suddenly there were Baker and Katagiri in a big hug, everyone watching and laughing. Katagiri said, “First time!” It was strange, these two bald figures, one short and in robes, one tall and in slacks. Baker moved into a flustered, stiff little speech about how “we are so very happy whenever you come.”

We got in John Bailes’ car and I heard Katagiri say, “I will hold,” and he took a bundle on his lap in the front seat. We were in the back. Sally Baker came too, and we left her with a friend in Sausalito. All the way we rode in silence. The windows got steamed up and the defroster was broken so I gave Katagiri a sock to keep John’s window clear. There were branches all over the road. For a while there had been a rumor that the bridge was closed, but it wasn’t. The wind was less, though it was still raining. On Page Street across from the Guest House one of the new little trees had blown over. When we got out on the corner in front of our door at the Coyotes,’ Katagiri said, “I will see you tomorrow.” And then he handed Bob the bundle and said, “These are Chris’s ashes”—the remainder, for Minnesota.

We took them upstairs and Bob went nervously from room to room trying to decide where to set them. There was some of the intensity of arranging the Guest House front room a few weeks ago. Finally he set the container on the coffee table in the living room, next to the peyote plants.

Monday, December 24

Back to the dentist, the day after the ashes ceremony. We skipped zazen. Just rapped on Katagiri’s door, gave him gassho goodbye.

Christmas had been far in the background for us, and the day Meg took me shopping it seemed an odd thing to even be considering Christmas. But as usual decorations and carols were everywhere. Zen Center hadn’t done anything, except at Green Gulch, but perhaps now that it was Christmas Eve they were going to do something. The rain made it seem more Christmassy.

After the dentist we walked in the rain down California Street, and when we got to the Mark Hopkins suddenly decided to blow $10 apiece on their fabulous buffet. Even though it was rainy and cloudy we enjoyed our corner table. We were still talking about the ceremony. We rehashed Reb’s fall downstairs over and over. Bob has nicknamed him Supermonk.

When we got home Bob was tired so we crossed our names off the signup sheet for the Zen Center Christmas dinner tonight, and Bob went to bed.

I had a conversation with Meg; she and Marc had been in LA and missed the ceremony. Also with Brian Unger, who missed it because he had dinner prep.

I couldn’t find the medicine for Dodger’s runny eyes so called Peter and Marilyn in Ohio.

I also had a conversation with Okusan. It was to ask her to make sure Chris’s Buddha went to Elizabeth Baker on July 2. Bob had left the figurine when we vacated Chris’s room for the Japanese student Michiko. He assumed that somehow, just because he had mentioned to Murayama Shoki, and perhaps also Reb, that he wanted to give the Buddha to the Bakers’ baby, that he needed to do nothing further. “But how is Elizabeth going to get the Buddha in July?” I kept asking. Shoki had long ago returned to Japan. Finally Bob agreed something else should be done, and I hit on asking Okusan to handle it.

So one day, as I was over at City Center checking for mail and heard the pat-pat of Okusan’s sandals going by, I turned and followed her upstairs. At the top she turned right to go to her quarters, and I called to her and she stopped and smiled.

Then there was an awkward moment. I was standing in front of the Suzuki chapel, where it was customary to gassho to his statue before crossing in front of it to go left, as I would have to head for Chris’s room, for instance. I wasn’t going left, but somehow, perhaps because I’d done so often before, I gasshoed again, right in the middle of speaking to Okusan—then thought, “No! How foolish!” because this was Suzuki’s wife! I got flustered.

But Okusan just started talking to me. I stopped worrying about my awkward gassho, because she was in a half-gassho herself, as she stood there. Her whole posture was a half-gassho, which made me half-gassho too. She said she was sorry to have missed Chris’s ashes ceremony the day before.

“Well,” I said, “You would have gotten very wet!”

“Yes, Katagiri-roshi told me this morning there was a very big storm. ‘Good storm!’ he said.” She gave a big smile. Even when her features were almost immobile, her face somehow twinkled like a lightbulb. That made me relax.

Then I started the problematic subject of Chris’s Buddha. I said Bob wanted the statue to be presented to Elizabeth Baker on her birthday in July, but this was not an easy concept to get across the language barrier, particularly as it was such a novel idea.

“Ah, then you take it back now, and in July you give it,” she said. “You want key for Michiko’s room, but she is out of town at a wedding...”

“No,” I explained, and got nervous again. “Bob would like it to stay in the room, and then go to Elizabeth in July.”

“Ah, so!” said Okusan, looking puzzled. “Ah, so!”

“Is that all right?” I asked doubtfully.

“Yes,” she replied. “I will take care.”

I then explained we would soon leave San Francisco. I couldn’t tell if she was already aware of our plans. She said she was about to go to Los Angeles for the family wedding too. She explained that preparing for the trip was why she couldn’t go to Green Gulch the day before.

“Too many ceremonies lately,” she said. “Too many parties.”

She wanted her regards sent to Bob. She also wanted him to know that at the time of the ashes ceremony she was offering incense and prayers for Chris here at Zen Center, during the big storm.

Tuesday, December 25

On Christmas Day we awoke at 8:00 or so. The sun was shining on the wet streets and Bob said, “Let’s go climb Mount Tam.” We took the bus and spent the day hiking and remembering how Chris had enjoyed the mountain woods. Then we returned hungry to the city and had a good dinner in Chinatown before taking a cab back to the slum. Later we read that three people in San Francisco were murdered on Christmas Eve.

Wednesday, December 26

We learned that it cost $650 to rent a truck and drive it to Minneapolis. For some reason nobody rented vans or anything smaller than a 12-foot-bed truck, and one dealer estimated a 12-foot truck would get 5 miles per gallon, which with gas at $1 would add over $400 on the 2300-mile trip.

So I spent several hours searching by phone for cheaper rentals, or for alternatives such as shipping Chris’s motorcycle and twenty 25-pound boxes so we could rent a compact. One depressing discovery was that renting a compact cost almost as much as a truck.

Then in the Yellow Pages I hit a list of “drive-away” companies. After calling four or five of them I found one in Oakland that had a vehicle going to northwest Minnesota—and the vehicle was a pickup truck! The only way to reserve it was by $150 cash deposit, so we had to get to this dumpy, fly-by-night-looking upstairs office a few blocks away from the 19th Street BART station. We returned just before dark to Peter’s apartment.

I had just made tea and we were sitting around his office with the heater on and Fudo on my lap, when Meg knocked on the door. She stayed about an hour, sitting with me on the floor at Bob’s feet, because he was in the only comfortable chair, and listening to him talk about Katagiri’s excellence, Chris’s high regard for his strong practice, and Katagiri’s high regard for Chris.

She and the princess were the only people still in the Guest House. Marc had gone to Green Gulch to assume duties as director. She would stay here a few more weeks before joining him. As usual, she indicated neither good nor bad feelings about any of it. I suggested Bob and I go sleep at the Guest House because it was dangerous for two women to be alone. Meg looked a little frightened when I said this, but declined. We walked her home though. Before we left we passed a poster Peter had of an angry Khali-type deity. Meg bowed to it, and said jokingly, “Well, better bow to the black Buddha.”

Thursday, December 27, 1979

We haven’t gone to zazen all week. We have done enough with Zen Center, Bob said.

Across Laguna Street from Peter’s we watched a young Black caretaker and his huge police dog. He carried a knife. He would have been an ally, Bob noted, if the caretaker’s association idea had taken hold. Sometimes we still thought of staying. But we were going to go.

I made phone calls to settle the question of Chris’s motorcycle, which was still in the name of the friend he bought it from, Stephen Scheatzle, because we couldn’t find the title papers. This seemed to be easily resolved and I talked to Steve by phone. But we had to go to a Department of Motor Vehicles office on Baker and Fell Streets at the end of the Golden Gate Park panhandle. And that required a bus ride up Haight Street. We got our bus and rode about five minutes to Baker. As we went past Chris’s death place, once-beautiful Victorian houses lined the street, like the Guest House but with peeling paint, names scrawled on the walls, and broken windows. Lots of trash in the gutters. Here and there were a few insolent men or a mean-eyed woman or kids on roller skates, some White but mostly all Black.

The motorcycle red tape was handled easily. We laughed about how many times Chris had been right there filling out forms on his menagerie of vehicles. And when we were done our bus took us back to Zen Center without incident.

At 5:30 pm I went to evening zazen. It was just one period, with no drums, no chanting, no Reb, no Baker-roshi, and very few priests or robes. Just zazen with neighborhood people in regular clothes after work.

Friday, December 28, 1979

Back at the dentist again. They always played good music there, at least. One day it was Joan Baez, which made me think how different this California had been from the one in my dreams.

Last Monday, when the dentist put on the crown and five fillings in one hour, no Novocain, he played Mozart, which was very nice. There was also a skylight, with raindrops on rainy days, and often on sunny ones a cat.

I lost the tooth that died. I no longer have bruises on my face but have to display a gap in my front teeth. Meg made a joke when she discovered it.

Saturday, December 29

The last few days at San Francisco Zen Center were relaxed. We mostly packed, and also cleaned Peter and Marilyn’s apartment we were leaving. We sent goodbye notes to Michael and Jan, the sailors who had been interested in bringing our boat back from England had we stayed in San Francisco. One day when Bob was out starting Chris’s motorcycle in the garage and saw Reb Anderson, he invited us to a children’s variety show, which he attended with Rusa. Yvonne Rand never telephoned for the lunch date she had mentioned. We never saw Richard Baker again. After Chris’s ashes ceremony Bob stopped sitting zazen as we had been doing at 5:00 every morning since late November. I only went to a couple more sittings and to a Steve Weintraub lecture.

Our last night at Peter and Marilyn’s, we heard shouts in the street. Some Blacks had driven up Page, and a White loudmouth across the street from Zen Center shouted at them to slow down. The Blacks got mad and stopped their car, and a fight might have ensued, but a crowd of perhaps a dozen Zen students leaving an event immediately went over, among them Meg and Marc, Linda Cutts and Robert Lytle.

As we watched from the Coyotes’ upstairs window on the corner of Laguna and Page, we saw something the crowd below didn’t see: another young White man, drunk, on the sidewalk farther down Page was calling to a Black man, “Nigger! Come and hit me, nigger!” I put up the window to shout for help. But then the Black went over and just shook the other teasingly, grabbing his lapels and pretending he was about to punch him. We then realized it was a gay couple. One ran away across Page and the other followed, and that caught the eyes of the Zen students. The first fracas had cleared up, so the Zen students began running down Laguna and shouting, “Hey!” at the pair who seemed to be fighting. They got as far as Oak before the lovers, prancing and skipping, disappeared, so the students walked back to City Center.

Sunday, December 30

We saw Peter and Marilyn briefly when they returned from visiting her family in Ohio. John Nathan brought them from the airport and they seemed happy to be home. Peter and Marilyn had us in and the conversation was warm; he even looked disappointed that we were leaving town. After the lunch at Greens, he had thought Richard Baker’s words of welcome would have kept us in San Francisco. Bob explained that they did not, and that he wanted to finish Lila before working on a film.

“So you think it’ll take a year to finish the book?” he asked, in a warm but serious tone. Bob said it could take longer.

“Basically things are the same with us as when you left,” I told Peter, “except we are calmer.”

Peter looked at Bob’s beaming, relaxed face and said, “You sure are.”

We told them how we’d made full use of the apartment-sitting, enjoying their private photos and getting a taste of their past. We told how Katagiri had come for tea and we had shown him their altar and peyote garden. We discussed the pros and cons of Zen ritualism which Bob had found to be the bane of both Minneapolis and San Francisco Zen Centers. Peter was more tolerant. Marilyn said many Americans loved rituals at places like their Kiwanis Club, and she loved them since her days as a Campfire Girl.

“When I first came here I couldn’t hack the rituals,” Peter said. “But it got so they helped me see into the nature of myself, through identifying my resistances. Each time it is time to gassho I have to say, ‘Okay, who doesn’t like this?’”

Peter gave us a special round, black stone that looked like a crescent fused into the edge of a smaller circle. It came from a river in Oregon and he had had it on his altar for five years. “My stone will bring you good luck.”

We spent one last night at the Guest House, back in the beautiful large front room where we had begun. Meg invited us out to see a movie along with Neil Rubenking and his fiancée, and we all had supper and hung out afterwards at City Center with four or five other Zen students.

December 31, 1979, to Calistoga, California

We picked up the truck from the drive-away company and returned to load Chris’s possessions. Bob was just getting used to driving the truck, and as he parallel parked, a Black lady neighbor came over and criticized him for going over the curb with one wheel. Soft-spoken but tough, she was a fat, church-goer-type, conservative looking; her husband remained in their car. She told us she had lived there 35 years and every time the curb got crumbled, the city made her repair it. Bob apologized and told her he was the father of the boy who was murdered.

Neil Rubenking had talked about getting a group together to hoist the motorcycle into the truck. But he had confused the time for our departure so the crowd of helpers fell through. He found a heavy plank about 10 feet long for a ramp, and he and Peter, Bob, and a guy named Don from the grocery store and I rolled Chris’s bike into the back of the truck. Then Bob and I went up to Peter’s apartment and down again and again, loading the two dozen or so boxes in back with the bike.

It was one of the few times since arriving in November that we spent time out on the street near Zen Center without worrying about our personal safety. Maybe we were getting used to it; maybe it was that we knew we were leaving. A few people came to say good-bye. Zen student Barbara Horn gave me a package containing two bars of Chinese “Bee and Flower” sandalwood soap wrapped in colorful paper, the kind that had been in our room in the Guest House. Meg threw her arms around Bob twice and gave us an extra thermos bottle. The people who acted like they cared if they saw us again were Peter, Meg, John Nathan, Barbara Horn, and Don in the grocery store. And also David Chadwick. He gave us a warm farewell and said, “I’ll miss you guys.” We kept saying, “We think we’ll be back, maybe.” I wanted to say goodbye to Reb but couldn’t find him, so I sent him a note saying, “Bye, Reb. Happy New Year. See you later. Love, Wendy Pirsig.”

We left San Francisco foggy and showery around 4 pm. As our truck drove slowly across the red bridge we were unable to see much of anything at first. Then hills appeared, looking like giants were crawling around underneath light green blankets. There was a tree Bob said was some kind of California oak. By dusk we were winding under a full moon through an other-worldly wooded ridge between Sonoma and Napa Valleys, near Santa Rosa. There were wispy fogs and full creeks and craggy crags.

“The rainy season has started,” Bob said. “In summertime this all turns brown. This is so different from southern California, so much older. Robert Louis Stevenson lived here in stagecoach days. There’s a monument to him a few miles from here.”

It was good to be on the road and we were in good moods. We found an overpriced steak dinner where New Year’s celebrations were going on. We talked about the year and the other three New Year’s Eves we had spent together, and about the departure of the 1970s.

Between us riding in the truck was a woven straw basket we bought in Chinatown. It contained Chris’s ashes, a knit bag with his sewing kit, and the wool scarf he had worn in Maine with us last winter. Behind the basket, riding flat against the seat, was Katagiri-roshi’s calligraphy protected by a pillowcase. Underneath the basket was a box of Chris’s fragile Buddhist altar things. On top was placed his white straw Panama hat. We laughed at how the whole pile resembled a little idol sitting between us, and Bob said it made it feel like Chris was with us.

We got off the freeway and began the mountain road. But when we got to a motel and Bob started to bring the idol into the room for the night, he stopped and said, “That’s silly. It is just an idol for us. It isn’t Chris.”