|

I got to share some highlights of Marilyn’s progress the next year

when I was director. By then she knew more about Tassajara history

than anyone I knew except Jack. I admired her for sticking with it,

and felt we were kindred spirits in that I was focused then in my

free time on studying Zen writings and chants in the original. I saw

in Marilyn that same sort of drive and suggested that maybe we had

the research gene.

After that year I didn’t live at Tassajara but returned for short

stays in the summer and sometimes would be there when she was, her

store of knowledge about Tassajara’s past ever vaster. I lost track

of Marilyn but would think of her when I’d pick up the scrapbook

she’d left us with historical clippings, photos, and stories.

In the late 1980s I got into writing about my experiences in Japan

and Zen Center and about the life, teaching, and community of the

San Francisco Zen Center’s founder, Shunryu Suzuki. A few websites

grew out of that work. One, cuke.com, included interviews and

background. Early last year I decided to create a page for pre–Zen

Center Tassajara history to gather in one place what there was here

and there on the site and elsewhere within easy reach. I remembered

Marilyn and her work and decided to contact her. I sent a message to

Leslie James, a senior teacher in Zen Center, who along with her

husband Keith Meyerhoff has been living at Tassajara and Tassajara’s

way station at Jamesburg for many years. I learned then that Marilyn

had passed on just half a year prior and that there had been a

service for her at Tassajara. It was sad news to hear and I wished

I’d thought of contacting her much earlier.

I brought up with Leslie the possibility of getting Marilyn’s

material scanned and preserved better, something that I’d thought

about for years. I was relieved to learn that Marilyn’s friend Mark

Stromberg had just recently contacted Keith to discuss making

Marilyn’s scrapbook more widely available. Before long I was

corresponding with Mark and then Marilyn’s son Larry Burns. Each of

them sent me a

pdf

of slightly different versions of her book. Larry and his sister,

Lee Doyle, wrote a touching remembrance of Marilyn that now resides

on a page on cuke.com for her and this book

(www.cuke.com/tass-marilyn). In it they wrote:

She was, in many respects, while quite outgoing, a very private

person. She was a maverick in all things, refusing normalcy,

distrustful of the status quo. She loved gardens, but more so the

notion of a hidden courtyard with thick overgrown ivy on high walls

separating, as well as protecting her from the world at large. She

was an intensely loyal, family-centric person who raised five

children, two of her own and three from her second marriage.

From the mid-1970s through the early 1980s, she traveled to

Tassajara on weekends during the guest season—May to September.

While practicing Zen, she began writing the history of the Hot

Springs. She took to traveling widely in Monterey County at every

chance, interviewing anyone and everyone who’d been part of the

place, from the stagecoach drivers to the cooks. She documented

conversations and stories, collected boxes of pictures, and

passionately began writing an important part of California history

with the skill of a scholar.

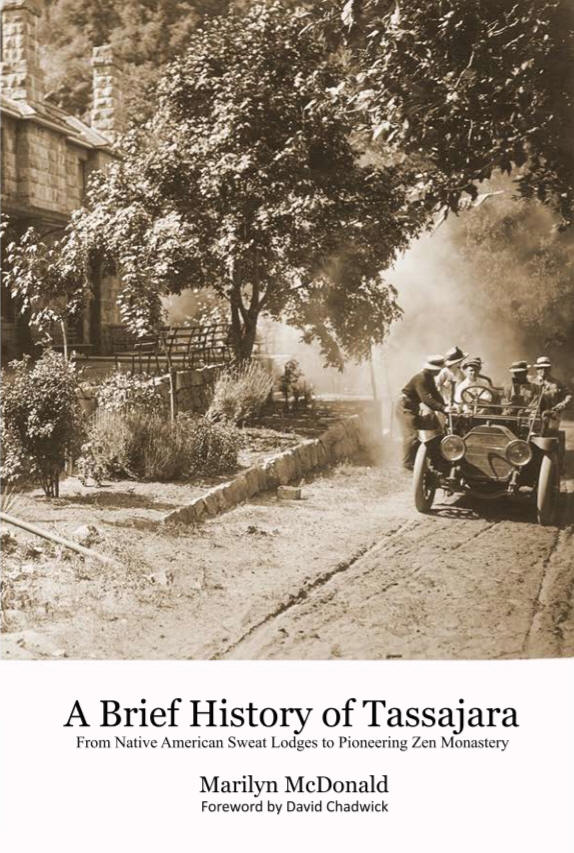

Now I find myself back again with Marilyn in the intriguing

narrative of this book. I imagine times when there were grizzly

bears, trappers, a creek full of fish, a narrow trail leading in

just wide enough for a horse, the labor intensive building of the

road, the early guests camping out in tents, the twelve hour trip in

on the horse drawn stage from Salinas, the early cars, the bootleg

whiskey guests would sneak in, the outdoor dance platform, the great

old sandstone hotel, and the most evocative—contemplating the

unknown thousands of years the Esselen and other Native Americans

came for the sacred waters and purifying steam in sweat lodges.

Marilyn had a clear eye and tells this story as it was told to her

by people and news clippings—without any romanticizing or

unnecessary elaboration. She did a good job on the final brief Zen

Center section. I was at Tassajara from a few months after it was

purchased and can vouch for most of what she wrote. I also checked

things out with others including Tassajara’s first head monk and

Suzuki’s virtual co-founder of the place, Richard Baker, the

director for the first few years Peter Schneider, the first head

cook Edward Brown who had worked in the kitchen there the year

before Zen Center acquired it, Alan Yehudah Winter who was there

very early on, and Leslie James for the later years. I found that

people were delighted to be reminded of those early Zen days at

Tassajara.

A meal chant used by practitioners at Tassajara has this line:

“Seventy-two labors brought us this rice. We should know how it

comes to us.” Many labors likewise brought us Tassajara in unspoiled

condition after being tended for millennia by Native Americans and

for a century by immigrant stock. In Buddhism, caring for the

physical space one inhabits is an integral part of the practice.

Shunryu Suzuki said, “Cleaning is first. Zazen (meditation) is

second.” This book reminds us that while we may have brought a new

spiritual lineage into that valley, it met there the ancient spirit

of the place and the people who came before.

David Chadwick |

During

During