|

A 1973 interview with Hakusan Kojun

Noiri discussing Shunryu Suzuki

These are the exact notes that were taken that day as I received them in 1994 from Peter Schneider. Hoichi is Hoitsu Suzuki, Shunryu Suzuki’s oldest son and dharma heir. Peter and Jane are Peter and Jane Schneider. Peter had been ordained as a priest by Suzuki. Carl Bielefeldt was a student of Suzuki’s who went to Japan to study Zen and who there married Fumiko. He is now a highly respected Soto Zen and Buddhist scholar and professor at Stanford University. Noiri Roshi is a highly respected priest in the Soto sect in Japan. I know this because of how highly Soto monks I knew spoke of him when I was there. Daiji and other monks at Shogoji in Kyushu, Japan, where I was in 1988 thought of Noiri as the most respected living Soto Zen priest. I think the word "revered" would be appropriate. In the introduction to Zen Mind, Beginner's Mind, Richard Baker said of Shunryu Suzuki that he was "already a respected Zen master in Japan." Noiri is the only Soto priest I know of who seems to concur. But that's a pretty good recommendation. Today, August 9, 2005, I put these notes on cuke.com - DC

NOIRI-ROSHI AUGUST 3, 1973 [Hoichi-San, Peter, Fumiko, Carl Bielefeldt, Jane talking about their untaped meeting with Noiri] Beginning in 1946 the temple of Kishizawa-roshi, Gyokudenin, is a temple under Rinsoin. Consequently at New Year's time there was a natural connection between the two temples. Moreover Kishizawa-roshi was great Zen Master of the time, so he had a lot of contact with Rinsoin, even though Rinsoin was above his temple in the hierarchy. So Suzuki-roshi had the position of Koshi at Kasuisai [How many monks were there? What was it like there?] and after So-on-roshi's [Suzuki's 1st teacher] death (1 or 2 years after[?]) he went to Rinsoin. Peter: What was Suzuki-roshi's function as Koshi? Noiri: Teach meditation to Unsui [new monks], lecturer on the Buddhist priest's life, etc. Peter: Did he live there? Kasuisai or Zounin? Noiri: He was head at Zounin and lived there and went nearby to Kasuisai to teach. Because of fact of being head of Rinsoin, he never lived with Kishizawa-roshi and didn't commit himself to Kishizawa-roshi as his disciple, but as head of Rinsoin had to attend to his own duties, but went to Kishizawa-roshi when some crisis or turning point in his own practice came up or for a question. Suzuki-roshi forty years younger than Kishizawa-roshi. In addition to relation they had (because Suzuki-roshi head of Rinsoin) Suzuki-roshi came to Kishizawa-roshi for his own questions and also he came once a month to Kishizawa-roshi lectures. Suzuki-roshi came as often as possible to those. So basically he (Suzuki-roshi) had those two types of student relationship with Kishizawa-roshi. Carl: Were the lectures of Kishizawa-roshi at that time on Shobogenzo? The group that met once a month in which Suzuki-roshi often participated were made up of Kishizawa-roshi students who for one reason or another were unable to live and practice full time with Kishizawa-roshi. The lectures were about Zen precepts. The group of such students formed this group to continue studying with him. In Suzuki-roshi's shinsanshiki [mountain seat ceremony û installing him as abbot of Rinsoin] (usually person makes his own verse in ceremony) since he had such a highly respected and famous teacher, he (Suzuki-roshi) asked Kishizawa-roshi to write his verse for him, which was very unusual to do. Even though Suzuki-roshi was able to do it, Kishizawa-roshi did and this is now in his memoirs (Kishizawa-roshi's) [Can we get that?]. Rinsoin had a jukai [lay ordination ceremony] after his shinsanshiki (2 or 3 days after) and 300 or 400 people gathered at Rinsoin for one week. Suzuki-roshi thought this was a good opportunity to give Kishizawa-roshi's dharma to everyone. Kishizawa-roshi led this week session. These are examples of how Suzuki-roshi efforts to spread Kishizawa-roshi teachings to many people. Big precept ceremony at Jokoji and Suzuki-roshi went there as head of Rinsoin and most important person there. He was surrounded by many older and more experienced people all who were watching him. Suzuki-roshi's bearing through the ceremony (he was leading it) was very strong and profound and demonstrated how much he understood meditation. Particularly how he opened his bowing mat, zagu. Spring 1949 lectures by Kishizawa-roshi on Gakudo Yoginsu[?] and Jissoku[?] given at Rinsoin. [see immediately below] CONTINUATION OF NOIRI-ROSHI FROM BOOK II AUGUST 1973 Examples of the way in which Suzuki-roshi took every opportunity to spread Kishizawa-roshi's teaching. And the one example that he said was famous or not famous but important in the history of Soto Zen was that Kishizawa-roshi had discovered a text by Dogen called the Gakudo Yojin Jissoku[?] which was a new version. So Suzuki-roshi asked him to lecture on the texts at Rinsoin. And so for ten days they had a lecture thing with he thinks around 30 people or more of Kishizawa-roshi's disciples at Rinsoin. And this was, Noiri-roshi thinks, a sort of crucial event in the history of the scholarship of Dogen's studies. Another story that Noiri told about the relationship of Kishizawa-roshi and Suzuki-roshi, said to demonstrate Kishizawa-roshi's special kind of strictness also. Shortly after Suzuki-roshi had his shinsanshiki at Rinsoin, at the jukai 3 days later, over 400 people to receive layman's precepts, which goes on for a week to ten days. And Kishizawa-roshi came to that. And in the middle of that ceremony he scolded Suzuki-roshi, criticized him in front of everybody, for something he had done during the ceremony. Noiri-roshi wasn't in the room at the time of the ceremony so he doesn't know what it was. Hoitsu also didn't know, but his interpretation of it is that Kishizawa-roshi wanted to correct the entire ceremony, all the people in the ceremony, he wanted to give them some lesson, and he singled out Suzuki-roshi who was the top person there, the person who was responsible for everything and scolded him in front of everyone right in the middle of the ceremony. And in that way gave a lesson to everyone in the most dramatic possible fashion. But Suzuki-roshi immediately took the position of representative of the whole group and accepted the scolding with a gasho, without any anger, and Noiri-roshi gave this as an example of something that couldn't happen in an ordinary social situation. A Master couldn't, an ordinary person wouldn't scold someone in that situation, and the person who was scolded couldn't respond with that kind of understanding of not taking it personally. Carl: Noiri Roshi said without the precepts as given to you by a true teacher, that the sanmai, samadhi, that a student has is not the true samadhi passed down (from the patriarchs) . This is the meaning of Noiri Roshi's example of precept teaching, making the implication that Kishizawa-roshi and Suzuki-roshi were in the proper student-teacher relationship. Carl: Noiri Roshi also said that Kishizawa-roshi understood that Suzuki-roshi was strong enough to stand up as representative of the whole group, and be criticized in that way, that he had confidence in Suzuki-roshi to single him out and criticize him in front of everyone. As an example of how impressed Noiri-roshi was with Suzuki-roshi, Noiri Roshi gave the time when there was another lay precepts ceremony at Jokoji, a famous temple, to which many famous priests came, and since Jokoji was a subtemple of Rinsoin, in the very middle day of the precept ceremony, there was a part to which Suzuki-roshi had to come and be the leader, and Noiri-roshi was there at that time and said that what struck him about Suzuki-roshi was that perfection with which he carried himself. The way he moved, the way he handled his zagu, the way he bowed, these kinds of things were so perfect and the tempo just right for the situation, that he felt that this kind of perfection could not have been achieved in one lifetime, but was based on his practice from previous lives. In trying to describe Suzuki-roshi's special quality, Noiri-roshi said, that if you make a kind of artificial distinction in enlightenment, you can say that there are basically two types. One is the bodhi-type enlightenment, and the other the Nirvana-type enlightenment, and roughly the Rinzai style enlightenment can be called the bodhi-style and Dogen's enlightenment can be called the Nirvana. And this type of Nirvana-enlightenment has come down from Shakyamuni Buddha, a very profound stillness or peace that characterizes this kind of enlightenment was characteristic of Suzuki-roshi. One instance in which Noiri Roshi felt very strongly the feeling of this stillness in Suzuki-roshi, when once at Yaizu station they happened to pass each other and Suzuki-roshi just gave a quick greeting, hi, and went by him, and Noiri-roshi felt that deep profound stillness in Suzuki-roshi at that time and as he watched Suzuki-roshi go up the stairs to the platform he had a very deep impression of him that he can still recall today. In that greeting, although he just said hi and went by, the impression was that Suzuki-roshi was in that very simple way encouraging his own practice. Noiri-roshi was very busy at the time; he'd just published a book on Dogen's Eihei-Koroku, so he was very busy, was dashing past Suzuki-roshi and it was the contrast Fumiko corrects. He had just finished publishing this work and in the Suzuki-roshi greeting, what he felt was a kind of gokurosama, a thank you and encouragement for the work that he had done. Suzuki-roshi didn't say, "You did a good job," just "Hi," but Noiri-roshi felt Suzuki-roshi recognized the effort he had made and was not congratulating him but encouraging him. Then as he walked up the stairs he was left with this image of Suzuki-roshi which he can still recall today. We American students had probably also felt the same kind of thing, a very special kind of stillness and peace in Suzuki-roshi whether he is alone, sitting, walking, whether he is in the middle of a crowd, that same kind of peacefulness about him. This kind of peacefulness is the enlightenment of Dogen and we as students of Suzuki-roshi should continue this tradition and maintain this kind of still Nirvana enlightenment. The Bodhi-style of Rinzai Zen is often mistakenly considered to be the Zen type enlightenment and what is perhaps most attractive at first glance in Zen, a kind of flashy, quick powerful image that we have of a Zen Master. But if we think that this is all that enlightenment is, then we are badly mistaken. And as students of Suzuki-roshi we should try to maintain this Nirvana enlightenment tradition. Hoichi-san's interpretation is the relationship between the stillness that Noiri-roshi felt and the importance of the precepts in Zen practice. In Kishizawa-roshi's tradition the emphasis is upon zazen within the context of the precepts, zazen in daily life, so that the order of the daily life makes possible the emergence of this Buddha nature that Hoichi-san mentioned in the story of the monk who forgot his hat[?]. That kind of reawakening to what you already have becomes possible through the precepts working not just in your mind but in body, in your daily life, when your body is completely in accord with the precepts and your daily life is just this continuous practice of the precepts. Then the power of meditation comes out in this and you remember what you already have. And this is Kishizawa-roshi's teaching. Kishizawa-roshi is known for being very strict, but his strictness is not in any kind of physical strictness, like beatings or very arduous practice physically. The strictness is rather in maintaining the precepts. So Hoichi-san's explanation of this is in the context of an interesting thing that Noiri-roshi said about our responsibility as students of Suzuki-roshi. Noiri spoke about biographies of Zen masters. Basically it is impossible for someone to write about the life of a Zen master unless he himself has reached the kind of samadhi that the Zen Master has. In writing a biography, one of the reasons that he declined to give us any dates or facts was that he felt that unless the biography itself is written in such a way that the dharma of, in this case Suzuki-roshi, was transmitted through the biography, it was not really a Zen Master's biography, but just a worldly or mundane biography. In other words, the biography itself must be written in a way that will transmit Suzuki-roshi's dharma. But to write biography you have to meet many many people and that is a kind of practice for the disciple to meet many people and you may not get the right information, maybe just one out of ten, but in that way only can you write the biography. In that way he emphasized it is important to have accurate biography. In some sense what we said was one-sided, just emphasizing the spiritual. He says we should make a big effort and really search out completely the whole thing (it is not enough just to be enlightened). An example Noiri Roshi gave of respect which Suzuki-roshi had for Kishizawa-roshi was the fact that Suzuki-roshi used to take Hoichi-san to Kishizawa-roshi's temple when he was a very small child and before he could understand anything of Buddhism or Kishizawa-roshi's talks on Buddhism. He took him simply to have the personal contact with Kishizawa-roshi, believing that Hoichi-san would thereby gain some sense of Kishizawa-roshi's dharma, and Noiri-roshi said that Kishizawa-roshi once showed a sea shell to Hoichi-san and asked him if he wanted it and Hoichi-san said, "Yes," and that seashell now hangs in Rinsoin and Noiri-roshi said that he thought that when Hoichi sees this seashell today he is seeing in it both Kishizawa-roshi and Suzuki-roshi. |

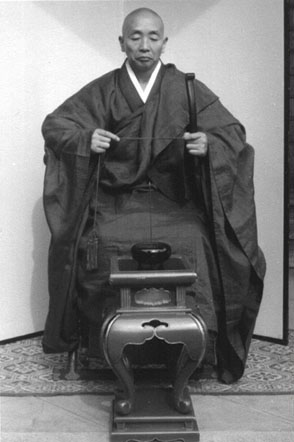

The

photo to the left comes from the

The

photo to the left comes from the