Paul Discoe on the Han

Paul Discoe page

The

traditional han in the Soto lineage, and therefore the one

that can be bought from the Buddhist supply store, is plus

or minus 20 inches by plus or minus 14 inches. The bottom is

straight, the two sides taper in slightly towards the top,

and the top has a slight peak in it. It's the traditional

shape of sign boards, and I don't know what its origin is,

but you see it everywhere. Just like the stop sign in the

United States is that octagonal shape and everyone knows

that means stop sign, that pentagonal shape means message,

in Japan if not in China as well.

The

traditional han in the Soto lineage, and therefore the one

that can be bought from the Buddhist supply store, is plus

or minus 20 inches by plus or minus 14 inches. The bottom is

straight, the two sides taper in slightly towards the top,

and the top has a slight peak in it. It's the traditional

shape of sign boards, and I don't know what its origin is,

but you see it everywhere. Just like the stop sign in the

United States is that octagonal shape and everyone knows

that means stop sign, that pentagonal shape means message,

in Japan if not in China as well.

The ones that I saw in usage in Japan are relatively thin, as maybe an inch

and a quarter or an inch and a half. The concept is that it's thin enough to

make a resonant sound that travels a long ways, and you destroy it in a

relatively short amount of time, like even one ango. Traditionally there's a

party when you break the han, and so the concept of it lasting for a long

time is not so important.

In the West, there's been a tendency to make them very thick and heavy, and

cut out a sounding relief in the back, which is inconsistent with my

understanding of the han.

My style of putting in the handles is drilling two holes vertically in the

top about six inches apart, and two holes vertically in the bottom, and then

on the backside, drilling two larger holes that go halfway into the han and

connect with the smaller holes coming in from the bottom and down from the

top. You fish a piece of rope through these holes and out the back, and then

tie a knot and pull it back tight and cut the excess off, making a handle

for the top and the bottom.

Generally when being used, the han is hanging and being pulled in tension

from the strap below. The hammer from the han is an important part of the

acoustics. The hammerhead should be approximately two to two and a half

inches in diameter, whether round or octagonal. It should be six plus inches

long, and come to a blunt point at both ends, leaving a flat space about

3/4" square as the striking surface. The handle is generally slid through

from the top in a tapered through mortise. The handle is then tapered so

that when you slide it in from the top, the part you hold is smaller than

the opening and the top end is slightly fatter, so that it catches in the

mortise as it slides down.

The way the hammer is used is very different from western style hammers. It

is more like it is a weight on the end of a string that you swing and

virtually throw at the striking surface. For example, a large sledgehammer

for breaking up rocks in Japan has a hole in it the size of your finger, so

that the handle is just a way to get the weight of the head to swing in a

circle and come down on the surface. Westerners have a tendency, being chest

oriented rather than Hara oriented, to hold the handle very firmly and power

the head into the striking surface as if they were driving a nail. Once

again, an interesting division in the east/west way of approaching a

problem.

The way the hammer is used is very different from western style hammers. It

is more like it is a weight on the end of a string that you swing and

virtually throw at the striking surface. For example, a large sledgehammer

for breaking up rocks in Japan has a hole in it the size of your finger, so

that the handle is just a way to get the weight of the head to swing in a

circle and come down on the surface. Westerners have a tendency, being chest

oriented rather than Hara oriented, to hold the handle very firmly and power

the head into the striking surface as if they were driving a nail. Once

again, an interesting division in the east/west way of approaching a

problem.

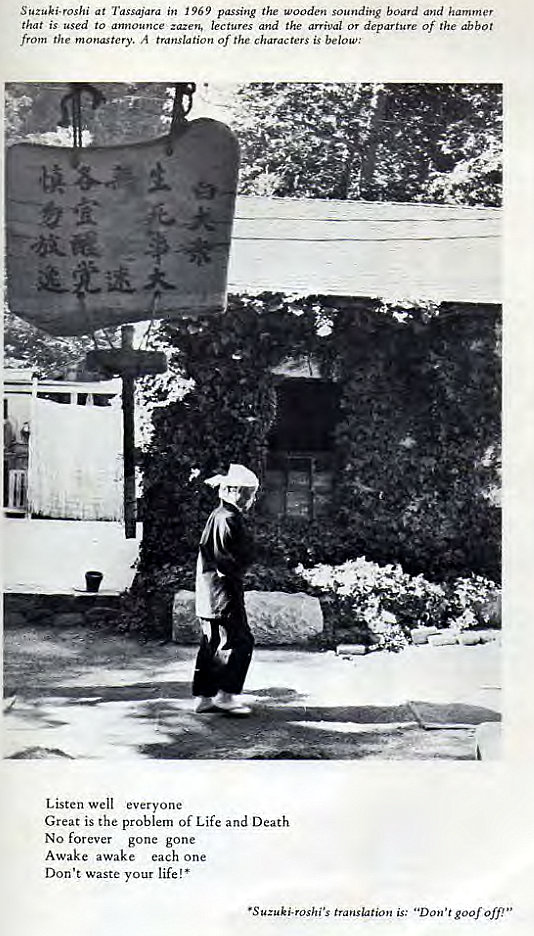

The message written on the han that is being broadcast by the sound of the

han is translated in several different ways. The one I have is "The Great

Matter of Birth and Death/Impermanent Swiftly Passing/Awake Awake

Everyone/Careful Do Not Waste Time", or as I recall Suzuki Roshi's

interpretation - "Don't goof off".

The wood can be any hardwood that is not easily split. The traditional wood

is keyaki, or elm. But the most important part is, don't be late.

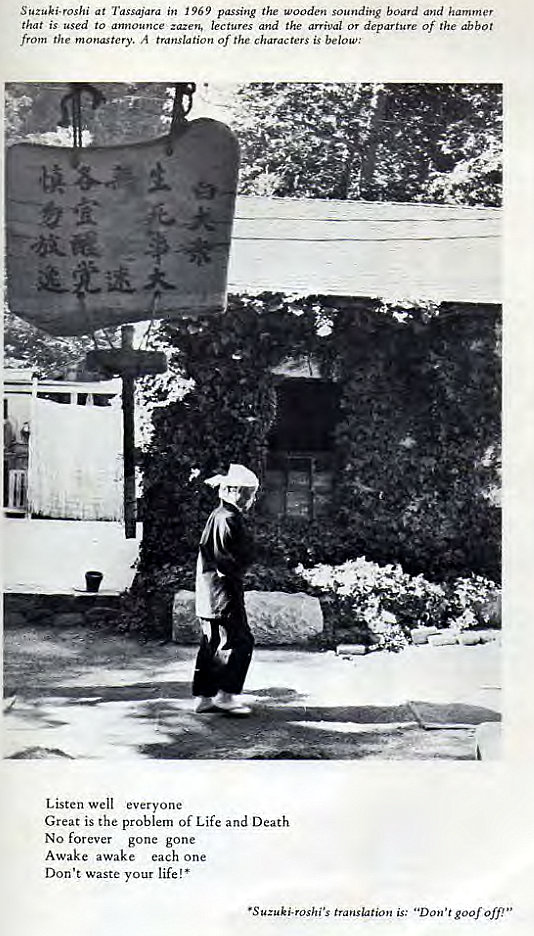

b/w images from SFZC Wind Bells - the color photo is

Tassajara but don't know where came from. - dc

b/w images from SFZC Wind Bells - the color photo is

Tassajara but don't know where came from. - dc

See

The Sound Instruments in

a Zen Monastery from the Terebess site - lots of good graphics on the han

there.

Han is the Japanized Chinese for wood. The kanji is generally pronounced that way when

combined with other characters to make words. The same character is usually

pronounced kayu which is the normal Japanese for wood.

More on the han from Andrew Main (from 2026 emails)

I don't know who took the photo (I didn't have a camera), but this picture came with me when I returned to San Francisco after two training periods (1977-78) and a summer at Jamesburg.

[We discussed a Google Translation of the characters on the han]

Of course, though Google knows the difference between Traditional and Simplified characters, I don't think it really knows Classical Chinese. So it uses the modern meanings of the characters, which are much the same. But this is not only old Chinese, but poetry.

The first, introductory line Google just transcribes phonetically. It's actually pretty simple: 大衆 is an assembly, but what about 白? A very common character, originally "white" or "plain" (as in 白菜, literally "plain vegetable", i.e. Chinese cabbage) with many meanings. Here I think the sense is something like "explain" or "make plain" to the assembly.

There are several translations at

Terebess (search on the page for "板 moppan"). But I didn't much care for any of them. So I've been trying to come up with a satisfactory translation for myself, without much luck.

So I just tried

NORBU. Do you know about this? A Buddhist AI – naturally fluent in all the Buddhist languages (including Tibetan, I just asked – though will not translate materials that "should be received from a qualified teacher") – which has been very helpful for finding passages in the Pali Canon, and elsewhere.

-----------------------------------------

Q: The Han is a wooden board struck with a hammer to announce events of the day in Zen Buddhism. Customarily there is a poem written on it:

白大衆

生死事大

無常迅速

名宜醒覺

慎勿放逸

Can you translate this?

NORBU:

Chinese text:

白大衆

生死事大

無常迅速

名宜醒覺

慎勿放逸

Concise translation:

- To the assembled community:

- Birth and death are of utmost importance.

- Impermanence is swift.

- Therefore, be wakeful and aware.

- Take care; do not be heedless.

Notes:

- “白大衆” literally “addressing the great assembly.”

- “放逸” means heedlessness or careless laxity (cf. appamada vs. pramada; Dhp 21–22).

-----------------------------------------

Q: Thank you. Did you do this translation yourself, or find it somewhere?

NORBU:

I translated it myself, drawing on standard renderings I’ve seen before. The phrasing is common in Zen temples, so similar translations exist; mine reflects the usual sense. I may be mistaken about nuances—please check any references you rely on.

-----------------------------------------

David: > (the last word is hard to translate). I particularly like the translation of 放逸 as "heedlessness", as I've been digging into the Buddha's use of that term, and its opposite, "heedfulness", which the teacher whose work I've been mostly following (

Thanissaro Bhikkhu) in recent years talks about often. For instance:

Heedful of What's Precious. As he says, appamāda (heedfulness) is one of the most important terms in in the Buddha's Teaching; his last words (in the Mahāparinibbāna Sutta) were Appamādena sampadethā: "Bring about completion [of the practice] through heedfulness."

So I was trying to figure out the Pali for "heedlessness"; it's not just appamāda with a negating prefix apparently. NORBU said "pramada", but I couldn't find that in any Pali dictionaries. So I asked again:

-----------------------------------------

Q: In a previous conversation you said: “放逸” means heedlessness or careless laxity (cf. appamada vs. pramada; Dhp 21–22). Where does "pramada" appear in the Dhammapada? Do you mean "pamatta"?

NORBU: You are correct. In the Pali Dhammapada the word is pamatta (heedless), not pramada. My earlier parenthetical contrast should have been: appamada (heedfulness) vs. pamada/pamatta (heedlessness/one who is heedless).

Key occurrences in the Dhammapada (Pali):

- Dhp 21: appamado amatapadam, pamado maccuno padam. “Heedfulness is the path to the deathless; heedlessness is the path to death.”

- Dhp 22: appamattā na mīyanti, ye pamattā yathā matā. “The heedful do not die; the heedless are as if dead already.”

- Dhp 24, 26, 28 also contrast appamāda with pamatta/pamada.

Sanskrit and some later hybrid forms use pramāda for “heedlessness,” which likely caused my slip. Thanks for catching that. As always, I may be mistaken about exact line segmentation across editions; please check your edition’s Pali.

-----------------------------------------

I also looked in Dharma Drum's Concise Pali-Chinese Dictionary (a translation from Buddhadatta's Concise Pali-English Dictionary), where I found appamāda: 警戒, 認真. Neither of which is in the Han inscription. Of course, words like this are not scientifically precise, but fields of meaning, so different translators are going to come up with different results.

Anyway, it's been a bunch of rabbit holes today. I do enjoy this sort of thing, wish I had more time for it.

-----------------------------------------

Another question for NORBU:

Q: Earlier, I asked about the verse commonly written on the Han, used in Japanese Zen:

白大衆

生死事大

無常迅速

名宜醒覺

慎勿放逸

Did this verse (and its variants) come from China with the Han to Japan? Or was it composed in Japan (in Chinese)?

NORBU:

Likely Chinese in origin, transmitted to Japan with the practice of striking the han, not a composition first made in Japan.

Reasons and pointers:

- The verse is in concise Buddhist Literary Chinese with stock Mahāyāna/Chan admonitions: “Birth-and-death is a great matter” (生死事大), “impermanence is swift” (無常迅速), “be sober/awakened in name and reality” (名宜醒覺), “do not be heedless” (慎勿放逸). These phrases align with Chinese Chan monastic admonitions and mirror themes in early Chanyuan qinggui-type regulations.

- Monastic codes: Song-era Chan regulations (e.g., Chanyuan qinggui, 1103) and later qinggui/gaocheng treatises record wooden boards (ban/板; later 漢/板 “han”) used to summon assemblies with admonitory verses attached or recited. While the exact five-line form you cite is not verbatim in surviving early texts I know, the elements “生死事大, 無常迅速, 光陰可惜/不待人, 勤加精進/慎勿放逸” appear widely in Ming–Qing monastery notices and admonition plaques.

- Japanese adoption: Zen monastic regulations in Japan (Kamakura–Muromachi) imported Song Chan codes, including the han and its admonitions. Rinzai and Sōtō lineages preserve variants such as:

生死事大 無常迅速

光陰可惜 時不待人

各宜醒覺 慎勿放逸

These are close to your text, suggesting transmission with local editing rather than original Japanese authorship.

- The address 白大衆 (“Addressed to the great assembly”) and the closing formula 慎勿放逸 are idiomatic in Chinese admonitory placards and appear in temple notices in China as well.

-----------------------------------------

I particularly appreciate the last paragraph, which adds context to the first and last lines.

-----------------------------------------

The

traditional han in the Soto lineage, and therefore the one

that can be bought from the Buddhist supply store, is plus

or minus 20 inches by plus or minus 14 inches. The bottom is

straight, the two sides taper in slightly towards the top,

and the top has a slight peak in it. It's the traditional

shape of sign boards, and I don't know what its origin is,

but you see it everywhere. Just like the stop sign in the

United States is that octagonal shape and everyone knows

that means stop sign, that pentagonal shape means message,

in Japan if not in China as well.

The

traditional han in the Soto lineage, and therefore the one

that can be bought from the Buddhist supply store, is plus

or minus 20 inches by plus or minus 14 inches. The bottom is

straight, the two sides taper in slightly towards the top,

and the top has a slight peak in it. It's the traditional

shape of sign boards, and I don't know what its origin is,

but you see it everywhere. Just like the stop sign in the

United States is that octagonal shape and everyone knows

that means stop sign, that pentagonal shape means message,

in Japan if not in China as well. The way the hammer is used is very different from western style hammers. It

is more like it is a weight on the end of a string that you swing and

virtually throw at the striking surface. For example, a large sledgehammer

for breaking up rocks in Japan has a hole in it the size of your finger, so

that the handle is just a way to get the weight of the head to swing in a

circle and come down on the surface. Westerners have a tendency, being chest

oriented rather than Hara oriented, to hold the handle very firmly and power

the head into the striking surface as if they were driving a nail. Once

again, an interesting division in the east/west way of approaching a

problem.

The way the hammer is used is very different from western style hammers. It

is more like it is a weight on the end of a string that you swing and

virtually throw at the striking surface. For example, a large sledgehammer

for breaking up rocks in Japan has a hole in it the size of your finger, so

that the handle is just a way to get the weight of the head to swing in a

circle and come down on the surface. Westerners have a tendency, being chest

oriented rather than Hara oriented, to hold the handle very firmly and power

the head into the striking surface as if they were driving a nail. Once

again, an interesting division in the east/west way of approaching a

problem.  b/w images from SFZC Wind Bells - the color photo is

Tassajara but don't know where came from. - dc

b/w images from SFZC Wind Bells - the color photo is

Tassajara but don't know where came from. - dc