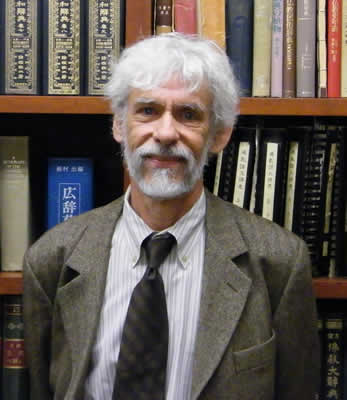

Carl Bielefeldt

Cuke Podcast reading from Carl's talk on Dōgen's Mountains and Waters Sutra 🔊

I remember Carl at Tassajara very early on. He went to Japan in the sixties and learned a lot, came back, learned more and became a professor at Stanford and leading expert on Dōgen, Zen, Buddhism, religion. He and his wife Fumiko were translators and interviewers along with Peter and Jane Schneider of Shunryu Suzuki's family members, and godfather at the SF City Center before Suzuki's death and with the family and Kojun Noiri a year after Suzuki's death.- dc [see Interviews] [See mention of Cal in Hoitsu Suzuki's Introductory Comments to the Japanese edition of Crooked Cucumber - and DC's comments on Hoitsu's comments.]

From The

Human Experience - inside the Humanities at Stanford University

From The

Human Experience - inside the Humanities at Stanford University

Religious Studies Expert - Carl Bielefeldt - bio, list of Carl's works, and a list of links under Prof. Bielefeldt in the News

Draft of Carl's 1998 excellent talk at Stanford Sati Foundation Shunryu Suzuki conference on Suzuki's historical and teaching background.

Carl has been involved with Gil Fronsdal to some extent with Shunryu Suzuki's college thesis. Here's a page for it with an outline and more info. The above Stanford Seti Conference talk starts with Carl discussing it.

Section of the Fall/Winter 1998 Windbell with Carl's Sati conference talk

Shunryu Suzuki teachers and heirs page

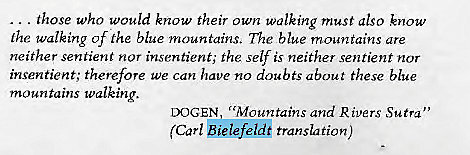

Transcript of talk

Carl gave on Suzuki at Tassajara July 21, 1999 on the Mountains and

Rivers Sutra

(with audio link) - Abridged version and whole talk

Two excerpts from the talk for Brief Memories:

Suzuki on this sutra and

on Shingon and Soto Zen

Carl's translation of the Mountains and Rivers Sutra

[here's

the page on net where it was downloaded from - ZMM.org]

From

Stanford's Dept. of Religious

Studies page for Carl

From

Stanford's Dept. of Religious

Studies page for Carl

Carl W. Bielefeldt

Evans-Wentz Professor (California-Berkeley)

Specializes in East Asian Buddhism, with particular emphasis on the

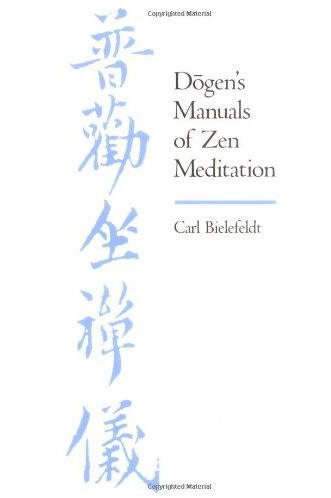

intellectual history of the Zen tradition. He is the author of Dōgen's

Manuals of Zen Meditation and other works on early Japanese Zen and

serves as editor of the

Soto Zen Text

Project Co-Director of the

Ho Center for

Buddhist Studies.

Professor Bielefeldt received his Ph. D from University of California at

Berkeley.

Curriculum vitae on Stanford site (on cuke) Publications on Stanford site (on cuke)

Dōgen's

Manuals of Zen Meditation -

UC Press link

-

Amazon link

Dōgen's

Manuals of Zen Meditation -

UC Press link

-

Amazon link

Carl is a co-author of Traditions of Meditation in Chinese Buddhism (Studies in East Asian Buddhism, No 4 - U of Hawaii Press link - Amazon link

Carl and his wife Fumiko did real time translation of interviews with Shunryu Suzuki's family, joining Peter and Jane Schneider for those sessions in 1971 and 1972. See Interviews on the right side, the Japan side that have *** after the title. I'm now (8-13-11) checking to make sure all of those interviews are on cuke. They were re-assessed with comments added by Fred Harriman in the late nineties.

Beyond Good and Evil by Carl Bielefeldt on Audio Download

The western notion of karma meaning "you sow what you reap" is simplified and untrue according to Professor Carl Bielefeldt, an expert on the history of Japanese Buddhism. Bielefeldt sheds new light on the often misunderstood Buddhist force and shows how it might fit into a higher ethical code. He invites his audience to step outside their own cultural domain and behold this intriguing way of thinking.

Shinyo-en Foundation interview with Carl Bielefeldt

Posted at their site on Jun 19, 2008

Shinyo-en Foundation

website

A

graduate of UC Berkeley, Professor Carl Bielefeldt specializes in East

Asian Buddhism, with particular emphasis on the intellectual history of

the Zen tradition. He is the author of Dōgen’s Manuals of Zen Meditation

and other works on early Japanese Zen, and serves as editor of the Soto

Zen Text Project. He is also the Director of Stanford’s Asian Religions

& Cultures (ARC) Initiative and Stanford Center of Buddhist Studies.

Recently, the Shinnyo-en Foundation provided Stanford University with

the Shinnyo-en Visiting Professorship Fund. Mariko Terazaki,

Communications Manager, recently visited the center and sat down with

Dr. Bielefeldt to talk about his work and the growing relationship

between the Foundation and the Stanford Center for Buddhist Studies.

A

graduate of UC Berkeley, Professor Carl Bielefeldt specializes in East

Asian Buddhism, with particular emphasis on the intellectual history of

the Zen tradition. He is the author of Dōgen’s Manuals of Zen Meditation

and other works on early Japanese Zen, and serves as editor of the Soto

Zen Text Project. He is also the Director of Stanford’s Asian Religions

& Cultures (ARC) Initiative and Stanford Center of Buddhist Studies.

Recently, the Shinnyo-en Foundation provided Stanford University with

the Shinnyo-en Visiting Professorship Fund. Mariko Terazaki,

Communications Manager, recently visited the center and sat down with

Dr. Bielefeldt to talk about his work and the growing relationship

between the Foundation and the Stanford Center for Buddhist Studies.

So Carl, thank you for agreeing to talk with us today. To begin with, would you tell us some background information about yourself and how you came to be working at the Center for Buddhist Studies at Stanford?

I became interested in Buddhism as an undergraduate at San Francisco State, where I began practicing Zen meditation and studying Japanese language. I then studied at Waseda University for a year and went into a Soto Zen Monastery for a year. And after that I really knew I wanted to study Buddhism in graduate school. So I came back, got married, enrolled at UC Berkeley, and, after going to and from Japan a lot and writing my dissertation with a professor at Kyoto University, I graduated in 1980. Afterwards I was offered a job here at Stanford and, since my wife and I enjoy the Bay Area so much, I said yes and have been here ever since.

Could you give us some information about the Stanford Center for Buddhist Studies and your work here?

When I first came to Stanford there was almost no graduate education in Buddhism. One of my dreams was to recreate the kind of program here at Stanford that I had been in at Berkeley, because it was so much fun and so interesting that I thought it would be great to do the same thing here. In the 1990’s, a private foundation approached us and said they would be interested in helping us start a center. At that time there were no centers of Buddhist Studies in American universities, but Stanford accepted the idea. We began in 1997; so we celebrated our tenth anniversary just last year.

What are the goals and objectives of the Center for Buddhist Studies?

The center has basically three different types of activities. The first is research support. We hope to foster research in Buddhism and the communication of that research. We do this by supporting visiting fellows, and by sponsoring conferences and workshops of scholars so they can come together and collaborate on common themes. One example of such a workshop will take place this summer around the Parinirvana Sutra.

The second type of activity is education. We support the curriculum by providing funds for extra courses, education in Buddhist languages that might not otherwise be taught (like Pali or Tibetan), and support for the graduate students in Buddhist Studies here at Stanford in the form of research or travel money, money for books, and other incidental grants.

The third type of activity is outreach to the public. We run a very rich set of programs that are open to the public and led by both scholars and Buddhist practitioners. For example, we recently had a workshop on styles of Buddhist practice. There’s a notion, particularly in America, that Buddhism is just about meditation and that, if you don’t like sitting on a cushion with your legs crossed, you can’t play in the Buddhist game. So we tried to broaden the public’s sense of the possibilities of Buddhist practice by talking about family practice, talking about social service and working in the community and other forms of practice that can be done by Buddhists.

What parallels and connections do you see between Shinnyo-en Foundation and your organization?

Well, certainly the social service aspects of our interests mesh perfectly with the Foundation. One of the things we’re quite interested in is how we can get beyond the elite sense of Buddhism. In America, almost all conversion to Buddhism occurs among white, urban, educated, affluent people. And it appears to be very difficult to reach beyond this group. Are there ways that an elite institution like Stanford, can find a voice that will carry beyond its natural constituency? Those kinds of questions really interest us. And I think the foundation is a fabulous example of this concern; in the ways you reach out into very different communities, different areas of American society, you are a great model for the rest of us.

Can you tell us a little bit about the Shinnyo-en Visiting Professorship Fund?

The visiting professorship will have a dramatic impact on the study of Buddhism at Stanford in several ways. First, it will expand our faculty in the field from three to four, permitting us to extend and deepen our coverage of the Buddhist tradition. Second, it will enliven our Stanford community, by bringing us each year a new colleague, with different expertise and fresh perspectives. Third, it will strengthen our ties with the broader community of Buddhist scholars, through the new friendships we make with our visitors. And finally, looking beyond our own campus, the visiting professorship will make a significant contribution to the international field of Buddhist studies, by providing the opportunity for scholars from around the world to spend a year studying and teaching at Stanford. The Shinnyo-en Visiting Professorship is indeed an exciting new page, for Buddhist studies and for Stanford, in our long friendship with the Shinnyo-en Foundation.

What were your impressions of the Six Billion Paths to Peace event in New York?

It was very impressive. Not only in terms of the number of people who showed up in the middle of Times Square, despite the cold weather; their enthusiasm was also quite remarkable. And the evening event was fabulous. In the organization of the event, there was what my mother would call a real sense of “class”; and, in the spirit of the event, there was real feeling. It was moving to hear about the various things people are trying to get done as their path to peace, and to see these things celebrated by so many people. Truly a moving event. Very impressive.

Now Carl, we’d like to learn a little about your interests outside of your professional work? What is the best book you have read recently?

There’s a new book out by Gary Snyder, called Back on the Fire, that I’ve enjoyed a lot. I’ve always liked Gary’s writing and got particularly interested in his work several years ago, when a student of mine organized a series of events celebrating Gary’s long poem, Mountains and Rivers Without End. Snyder’s world is a marvelous combination of Buddhist and American themes—a perfect read for a California Buddhist like me. Back on the Fire collects a number of his essays. It ends with a touching farewell to his wife, Carole Koda, a wonderful woman who died shortly before the book came out.

When not teaching, how do you spend your free time?

Two things I tend to do. One is to mess around with plants. Unfortunately, every year I get busy and neglect them; so my wife every spring asks me, “So what plants do you plan to kill this year?” I like taking care of plants because the health of the plants is sort of a measurement of where I am in my daily life. So, as the plants wilt, as they tend to do, it reminds me that there are certain things I need to take care of. The second thing I like to do is cook. My wife’s schedule tends to keep her very busy—particularly in the evenings, as she works in the theater—so I’m very often the one to do the shopping and cooking for us. And it’s great for me because I can leave my work in the 13th century and go to the store, buy something, and think up something to make that night.

Any special dish?

Well, what I like to cook the most are various kinds of pastries, like cheesecakes and flan.

And in closing please share with our readers, what is your personal path to peace?

Besides taking care of the plants and cooking for my wife, I try to build and maintain community in my work. The academic setting can be very cold: it looks like a paradise from the outside, but, like any institution when you’re on the inside, there are a lot of people living in this paradise that are unhappy, and there are a lot of institutional structures that tend to make people unhappy—pressures, competition, and the like. So one of my goals when setting up the center and the graduate program in Buddhist Studies was to try to make a place that students would look back on as one of the best times of their lives. A time when they made friends, had a sense of community and mutual support; not the kind of lonely, competitive struggle that graduate school can be for many students.

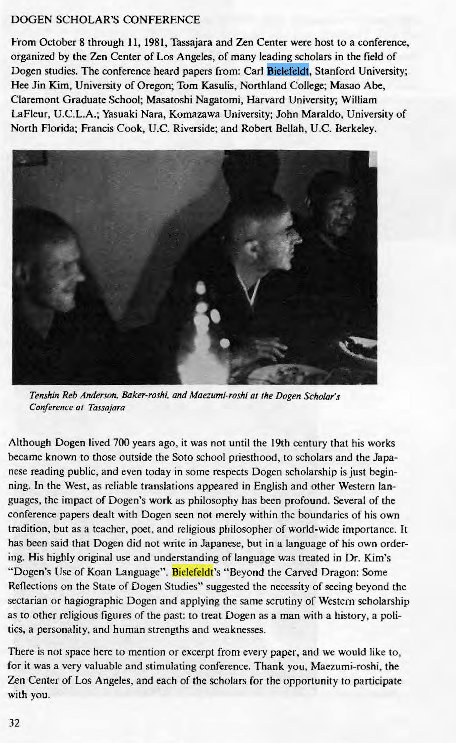

Carl Bielefeldt in SFZC Wind Bells

1974 Wind Bell (inside front cover)

Summer 1983 Wind Bell

Spring 1987 Wind Bell

Spring 1989 Wind Bell

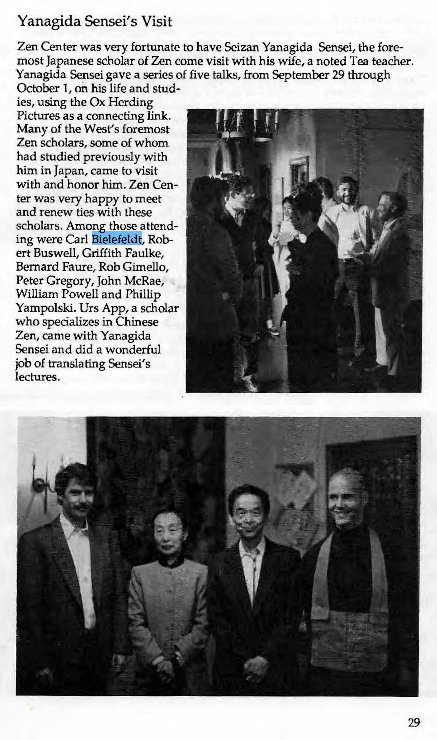

Fall 1989 Wind Bell

Zen Center News - Spring 1990 Wind Bell, p. 27

Vinaya Conference at Green Gulch Farm

Fall 1990 Wind Bell

Fall 1990 Wind Bell - pp. 21-23

Fall 1991 Wind Bell - pp. 28 - 32

Part of his review from Spring Summer 1998 Wind Bell - pp. 8-9

Fall Winter 1998 Wind Bell - Sati Center Conference on Shunryu Suzuki pp. 6 - 31 including Carl's talk on Soto Zen at the Beginning of the 20th Century - pp. 17-24.

As an Amazon Associate Cuke Archives earns from qualifying purchases.